1 – Introduction to the MEASA Region

The Middle East, Africa, and Southern Asia (MEASA) region is a relatively newly defined region but with long-standing significance. MEASA covers a large and diverse geography, spanning the historical Silk Road outside China and includes 88 countries, from Indonesia in the East, to Senegal in the West, from Turkey in the North, and to South Africa in the South.

While the region is vast, diverse, and has experienced a fair share of conflicts – some still active today – millennial old migration, trading, and political alignments, have created cultural and economic ties, bonding the region together. Today, the outlook may be more solid as many of these relationships are being further strengthened as bilateral economic activity and political cooperation are increasing, with countries such as the United Arab Emirates and Singapore playing active roles as financial and logistical gateways into the region that promote collaboration.

The three sub-regions (Middle East, Africa and Southern Asia) have distinctly different economic fundamentals, but also complementarities paving the way for symbiotic relations. The Middle East has vast oil and gas reserves and a significant deployable capital base held by the sovereign wealth funds (SWFs). Africa is home to some of the largest reserves of minerals and arable land. Southern Asia is a significant source of human capital (with many expatriating across the region) and a strong ecosystem for technological advancements.

Combined, the region’s resources are vast. In 2019, it was home to 4.1 billion people (53% of the global population) with a median age below 24 years, approximately 1 trillion barrels of proven oil reserves (56% of the global proven reserves), 5.4 million km2 of arable land (39% of the world total), and 36 Sovereign Wealth Funds with a total AUM of US$ 4.5 trillion.

2 – Engines of Economic Growth

While the region holds an outsized share of natural and financial resources, today it represents only 15% of the global GDP (total GDP of $12.6 trillion in 2019). However, with a young and fast-growing population and an average GDP per capita of just US$ 3.1 thousand (US$ 20.8 thousand in the rest of the world), the region has significant economic growth potential that is already starting to be realized. Over the last decade, MEASA real GDP increased by 51% (4.2% p.a.) versus 28% (2.5% p.a.) in the rest of the world. Further, the region is home to 9 of the 10 fastest growing economies globally.

As with all other economies, MEASA was severely hit by the COVID-19 crisis, but if we look at two key factors for future development, namely, population growth and the potential to converge towards more developed nations, the economic growth of the region is highly likely to continue outpacing that of the rest of the world.

2.1 Population Growth

The population of the region is projected to grow from 4.1 billion in 2020 to 7.6 billion by the end of the century (0.8% p.a.). As the population outside MEASA is projected to shrink from 3.5 billion to 3.2 billion over the same period, MEASA will represent more than 100% of the world’s population growth over the coming 80 years and will be home to more than 70% of global population by the end of the century.

In particular, Africa is expected to have a rapidly growing population. Of the 3.5 billion projected population growth, Africa will account for 2.8 billion. Nigeria alone is expected to grow from approximately 200 to 700 million over the period.

2.2 Convergence Potential

According to the standard model of long-run economic growth, poor countries should grow faster and eventually catch-up to richer countries if they share the same production technology and savings rates. While the GDP per capita is still very low at US$ 3.1 thousand, MEASA’s GDP per capita has grown much faster than the rest of the world, almost doubling (in real terms) over the last decade.

While the aggregate data seems broadly consistent with the convergence, we realize that initial conditions differ substantially across MEASA. The region includes some of the richest countries around the world (e.g., Singapore and Qatar with more than US$ 60 thousand GDP per capita) as well as some of the poorest (e.g., Burundi and Somalia with less US$ 300). The development trajectories have also differed significantly as the oil-rich GCC countries have grown earlier thanks to commodity exports, while the Southern Asian constituents have developed more recently and faster over the last decade due to technological innovation. MEASA thus comprises a well-balanced mix of countries with varying levels of economic development, and therefore a diversified basket of potential growth opportunities.

The size of the countries also varies significantly with the top 10 economies accounting for 2/3 of the total GDP and 2/3 of the total population with India, Indonesia, Nigeria and the Philippines in the top 10 both in terms of GDP and population.

So, what will drive MEASA future economic growth? The conventional engines of economic prosperity are international trade (i.e., focusing on sectors where countries have a comparative advantage), investment in human capital (e.g., education, labor force participation rate), and productive assets (e.g., infrastructure, technological advancements).

Looking at the openness of the economies, as measured by trade to GDP over the last decade, MEASA trade as a whole, amounts to 71% of GDP (including internal country-to-country trade) versus the rest of the world at 46%, suggesting trade plays a bigger part of the economic development story. Southern Asia is home to some of the most open economies with trade to GDP at 79%, Middle East at 68% and Africa 58%. Naturally, the countries rich in natural resources represent a significant share of the overall trade. The Arabian Gulf countries UAE, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, and Iraq, exported over $700 billion in 2019 and represented 17% of overall MEASA exports including in-region trade.

Interestingly, and adding to the integration with the global economy, the most open economies in the region have established a significant number of bilateral trading relationships – both between countries within the MEASA region, but also with external countries. As an example, the United Arab Emirates has more than 100 signed bilateral investment agreements (of which 37 have been signed in the last five years) while Singapore has over 50.14

As a second enabler of growth, the development of human capital, as measured by education levels, has seen a significant step-up over the past decades. Today, almost all of the population in the region receives basic education and most of the people now have attained secondary education level. Even the level of tertiary education has significantly increased, more than doubling over the last two decades and strengthening the potential for a sophisticated knowledge-based economy.

Recognizing labor force participation is a two-sided story with typically both very early-stage developed and highly developed economies experiencing higher participation rates, the average regional rate is generally on par with the rest of the world at 65% (versus 70% for the rest of the world in 2019). With the exception of countries with conflicts (e.g., Myanmar and the Democratic Republic of the Congo where participation rates have declined) the general trend has been towards higher labor force engagement.

Along with human capital, investment in fixed assets (e.g., infrastructure, land development, hospitals, schools, inventory, etc.) is a key ingredient for growth. Over the past decades, capital formation as a share of GDP has increased in MEASA faster than elsewhere, and in 2019 it represented 25% of GDP, a percentage that is on par with the rest of the world. Currently, US$ 3.0 trillion is being invested annually in capital formation across the region, but this is still much lower than the rest of the world where US$ 18.2 trillion is being invested annually. And as the existing installed asset base is significantly lower than in more developed markets, a substantial investment gap exists.

Technological breakthroughs, specifically solutions that reduce the need for large capex projects (e.g., distributed electricity generation, mobile data networks) will be part of the solution to fill the investment gap. In some cases, MEASA countries could even leapfrog their more developed counterparts by adopting state-of-the-art infrastructure in the absence of legacy assets. Among the MEASA sub-regions, Africa is the one that needs infrastructure the most. In 2019, 56% of the population did not have access to electricity (Middle East: 8%, Developing Asia: 4%), 70% were not connected to the internet and over 65% lacked access to an improved source of drinking water.

As a whole, MEASA is certainly not a technological laggard. Indeed, three out of the top ten countries in WEF’s 2020 ranking for ICT adoption belong to the region. Additionally, growth in research and development expenditure as a percentage of GDP is faster than the rest of the world, though needless to say from a much lower base.

2.3 – Economic growth leading to consumption growth challenges

Recent economic development has led to a significant growth in consumption expenditures, far outpacing that of the rest of the world. In MEASA, the consumption expenditures have grown at a rate more than double that of the rest of the world over the last two decades (5.2% versus 2.4% p.a.). The rise in consumption is generally associated with improvement in the living standards and as such should be welcomed. However, the widespread adoption of the “Western” capitalistic model of development without considering the negative consequences in terms of inequality, climate change, and other socio-economic risks could backfire given the sheer size of the population involved.

Enabling sustainable economic growth in MEASA will be a daunting challenge, especially as most of the countries in the region start the journey from poor records of sustainability scores. Using UN’s ranking of the current state of meeting the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), of all the countries where the SDG scores are measured, 61 out of the 73 (83%) countries under the world mean are based in MEASA.

Forward estimates around expected electricity demand and food consumption speak volumes for the extent of the challenge. The projected electricity demand for Africa alone (the region with the least developed energy infrastructure) is expected to increase by an average of 4% p.a. until 2070, causing required capacity to grow from 635 TWH/year in 2017 to 5,270 in 2070 if expected demand is to be met. As approximately 80% of the input for electricity generation today is fossil fuel based, significant effort needs to be made to foster more climate-friendly energy generation. Moreover, the expected increase in food demand will be a daunting challenge as consumption is projected to almost double by the year 2050 (from 2.9 quadrillion yearly calorie intake in 2012, to 5.2 quadrillion in 2050).

3 – Unlocking Institutional Capital for Sustainable Growth

A huge amount of capital is needed to transition MEASA to better sustainability standards. Crudely estimating required investment in the capital base under three scenarios: (i) sustaining existing growth in population but maintaining current GDP per capita (i.e., no wealth increase), (ii) meeting expected increase in population growth and increase GDP per capita at same rate as over the last 10 years (i.e., improving living standards in line with recent past), and (iii) meeting expected increase in growth and wealth while meeting the SDGs (i.e., achieving sustainable growth) suggests that the annual investment needed to grow from currently US$3.0 trillion to somewhere between US$4.5-5.5 trillion over the coming decade. According to the OECD, the COVID-19 pandemic has further exacerbated the investment shortfall, raising the overall annual SDG financing gap of $4.2 trillion.

The scale of the required investment outsizes local capacity, and while local governments and in-region SWFs are part of the equation, international institutional investors need to be mobilized as they are presently significantly underinvested in the region.

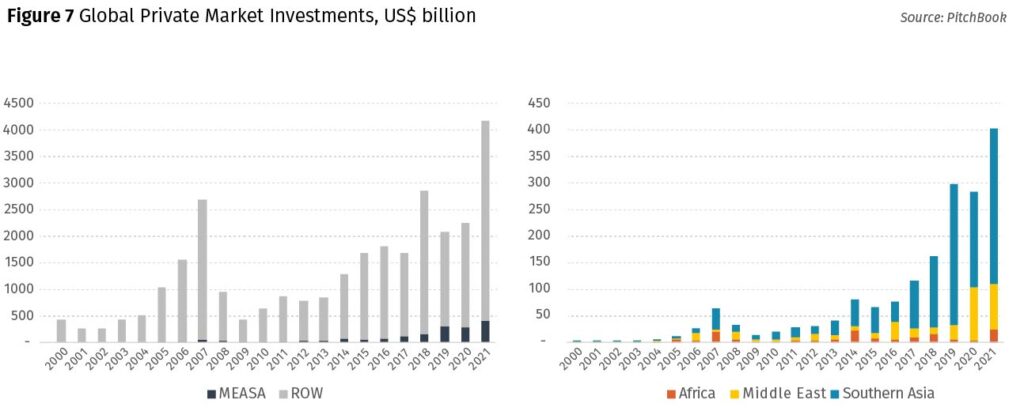

According to PitchBook in 2019, global institutional investors only allocated 1.1% of their global allocation into private market investments in the region (including commitments to General Partners in private equity, venture capital, angel, and infrastructure as well as direct investments) and over the last decade this percentage has consistently been below 3%. Further, of this allocation, the combined countries in Africa represent on average only 12% of the private market allocation to the region over the last 10 years. So, global institutional investors allocate consistently over the last decade a minuscule 0.25% to Africa – the continent that arguably has the greatest growth potential but also the highest need for sustainable economic trajectory. Furthermore, publicly listed companies in MEASA markets represent less than 4% of the capitalization of the MSCI ACWI (one of the most institutionally benchmarked index).

The MEASA underweight is indeed impressive: the global institutional investor community allocates around 2-4% into a region with 15% of the global GDP, 53% of the global population, and 100% of the global population growth over the rest of the century.

While institutional investors are significantly underinvested, we argue that the region could offer a highly compelling and diversified return opportunity across different asset classes. Particularly, those investors that are willing to take a longer-term view on the region and can tolerate the volatility that developing markets naturally contain, will be well positioned to generate attractive risk-adjusted return.

In addition, and increasingly important for most of the institutional investor community, the region offers an outsized opportunity to generate sustainable impact. The additionality effect of both the capital invested (funding where funding is scarce) as well as the investment management practices embedded in institutional investor practices (being a driving force in establishing stronger transparency, governance and impact alignment), would yield a highly outsized return in terms of impact. Arguably, providing the extra capital required (in a capital scarce country) to establish a gas-fired power plant rather than building a lower cost coal-fired power plant, generates significantly more impact than being the additional investor chasing an already overfunded wind farm project in the North Sea.

The MEASA underweight is thus a well-established fact. Institutional investors have so far turned their back on opportunities in the region, shying away from opportunities in public and private markets alike, in spite of the potential financial return and impact. Obviously, the reluctance is well grounded, and can be traced back to the economic and institutional barriers to international investment in MEASA.

4 – Challenges for institutional investors

The opportunity of cumulatively achieving attractive financial return (from growth and development prospects), a manageable financial risk profile (from diversification and low correlation to other investments), and high impact potential (from additionality effect) should be a significant investment rationale. However, it is also clear that investing into the region has not always been a smooth ride. The investors that are arguably needed the most – long-term institutional investors from outside the region – face the greatest challenges. With restrictive investment mandates, detailed due diligence processes, low risk tolerance (in particular for reputational risk), and little incentives to deviate from benchmark allocations, major changes in strategy are needed for the deployment of institutional capital at scale in MEASA. However, as many of the global SWFs and pension plans increasingly focus on sustainable investing, the region will become a target of choice if some specific challenges will be addressed.

Beyond the typical emerging market challenges (e.g., currency risk, higher volatility, etc.), we see four areas that need to be addressed to attract international investors to increase capital allocation to the region:

Firstly, with a total weighting of the MEASA region of less than 4% in the global indexes (e.g., MSCI ACWI) the region has remained under the radar for most global investors. Additional awareness, data, and research about both risk and opportunities in the region are badly needed. Hence, the definition of the region, and establishment of research initiatives such as the Transition Investment Lab, are important starting points for awareness building.

Secondly, while the need for capital is clear, actionable investment opportunities that can attract institutional capital at scale are still limited as the local investment community is nascent. Young local GPs typically cannot meet the expectations of an institutional investor deploying US$ 50-100 million tickets. Accordingly, alternative investment structures such as broadly diversified access strategies, fund-of-funds, LP-GP partnerships, need to be considered. In public equities, a few products have started to emerge, but are with noticeably few exceptions small and focused on sub-regions. As far as direct investment opportunities are concerned, additional scale and comfort are achievable through collaboration between international and local institutional investors. Beyond the well-established Singaporean- and GCC-based SWFs, more countries are establishing sovereign institutional investors and there are now 13 SWFs across Africa alone, and several countries are in the process of developing funds. This has brought the total regional SWF AUM to above US$4.5 trillion. The increased local institutional investor base helps drive quality of the local investment ecosystem and provides opportunities for global investors to invest alongside local ‘smart’ money.

Furthermore, the regional family businesses and family offices, that have a proven track-record as successful business builders in their home markets, are increasingly becoming institutional-style investors with professional investment teams, adding to the capability set of the local investor community.

Thirdly, as MEASA has been recently hit by high-profile investment scandals (e.g., Abraaj, 1MDB) as well as corporate scandals (e.g. NMC Health) global institutional investors have become more reluctant to invest due to reputational concerns. To reduce perceived/real reputational risk, strong due-diligence processes and increased transparency is required. In addition, we believe leveraging the ongoing shift towards sustainable investments among institutional investors, should be an enabler for increased regional focus, as the transactions demand additional scrutiny and reporting, while the impact intentionality might also be seen to further reduce reputational risk. Achieving this, however, will require better alignment around impact measures and KPIs that are relevant in a regional context.

Finally, as the region is large with many (often small) unique countries, understanding local regulations, tax systems, etc. is a significant hurdle. Moreover, complementing each country’s specific operating requirements, the evolution of well-regulated financial centers, such as Abu Dhabi Global Market (ADGM), established under common law and with a solid governance framework, provide global institutional investors a relatively easier gateway to invest into the region. In particular, as both local and international investment managers increasingly domicile in such financial centers.

5–Conclusions

The MEASA region is rapidly evolving as a result of growth in population and improved fundamentals. This trend is expected to continue, which will make MEASA the fastest growing region globally over the rest of the century. At the same time, the region is currently under-funded, which hinders the trajectory, but also creates risks of an unsustainable growth path that could lead to environmental and social risks that may spill-over globally.

We argue that there is a particular shortage of long-term institutional capital, most significantly from international institutional investors. We believe this source of capital would be particularly effective, not only for filling the funding gap, but also for catalyzing sustainable development whilst setting a higher bar for transparency and governance.

We realize that attracting international institutional capital requires overcoming a number of hurdles that are material today. Overcoming all of these hurdles will take time. However, starting the journey is important as each institutional dollar invested into MEASA will foster the transition to a more sustainable and equitable future.