Foreword

This persistent state of uncertainty hampers the ability of systems and institutions to effectively address the growing complexities of the multiple, unrelenting global challenges we face. As such, the polycrisis is not a passing phenomenon but rather an enduring feature of our times — a reality that businesses and investors must learn to navigate with agility, foresight, and resilience.

One particularly troubling dimension of the polycrisis is the resurgence of geopolitical fragmentation, which threatens to undermine global sustainability efforts. Tackling challenges such as climate change, macroeconomic imbalances, rising income inequality, food insecurity, and poverty alleviation demands multilateral cooperation and a degree of policy alignment that appears increasingly elusive. These issues, by their very nature, transcend borders and require collective, coordinated action. Yet, as rival blocs jostle for influence and economic self-interest trumps long-term stewardship, the prospects for meaningful global solutions appear to dim. Without a renewed commitment to international collaboration, the world risks lurching from crisis to crisis, with the polycrisis becoming a permanent feature of the geopolitical landscape.

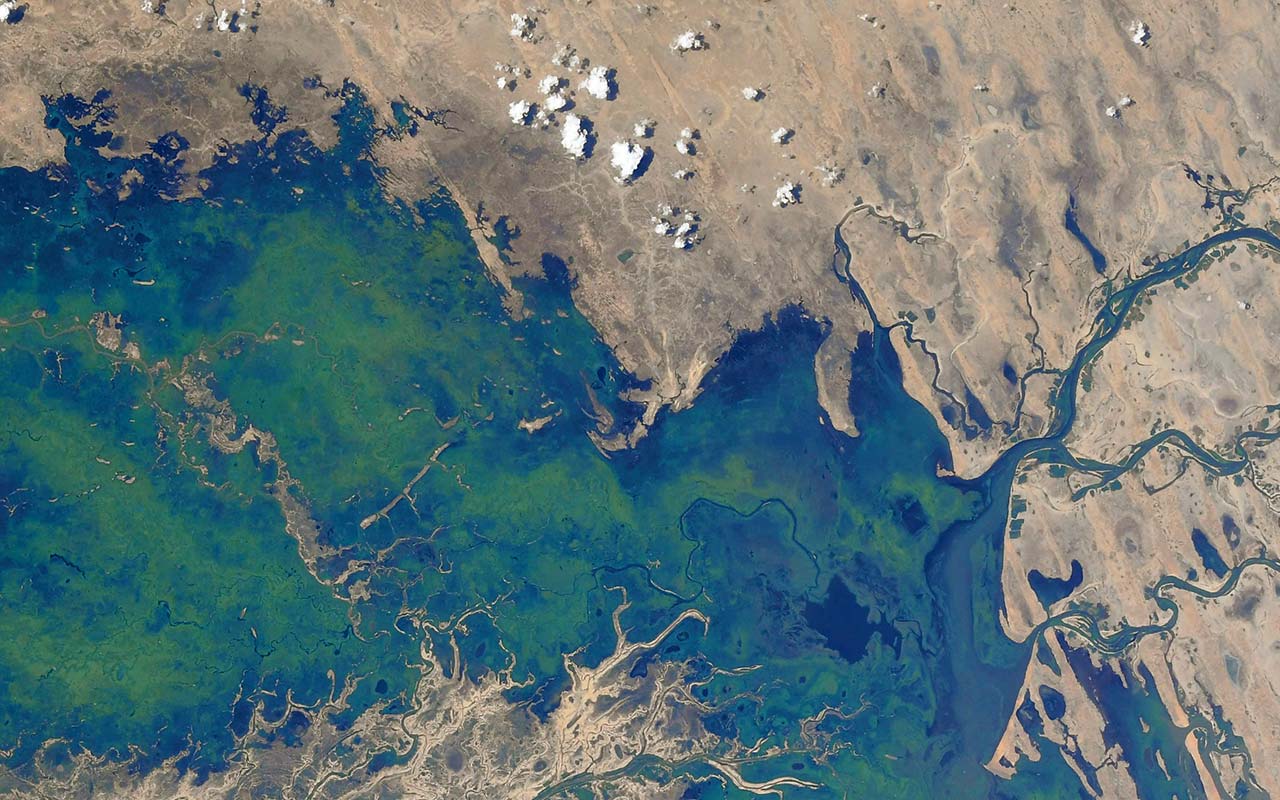

Some data are alarming. The 2025 update from the Stockholm Resilience Centre, which monitors risks arising from human pressures on nine critical global processes that regulate the stability and resilience of the Earth system, concludes that seven of these nine planetary boundaries have now been transgressed. In 2023 alone, climate-related disasters caused over $380 billion in economic losses globally, with less than half of these losses insured. The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) has warned of a potential tipping point in global insurance markets — a moment when escalating climate-related risks could lead to widespread market failure in insurance, making coverage unaffordable or unavailable in some regions.

For large institutional investors managing diversified portfolios across sectors such as real estate, infrastructure, energy, and industry, the financial exposure to physical climate risks is becoming increasingly material. Natural disasters capture headlines with their sudden, spectacular disruption, but every neglected global challenge exacts its own—often escalating—toll in economic losses and social harm. In short, the “cost of inaction” is no longer theoretical—it is an expanding line item on public and private balance sheets, reinforcing the economic case for faster adaptation efforts.

Yet within this turbulence also lies opportunity — for innovation, repositioning, and a structural rethinking of capital allocation. One promising signal is the continued decline in the cost of renewable energy, which is transforming power markets worldwide. As renewable electricity becomes cheaper and more reliable, it enables the development of large-scale, bankable projects — even in previously subsidized or risk-sensitive markets. Cheaper electricity is not only an input into sustainable development but also a key driver of productivity. The struggle of advanced economies such as Germany — facing high energy costs in the wake of the Russian gas transition — illustrates the link between affordable power and long-term competitiveness. At the macro level, a weakening U.S. dollar is beginning to shift the global investment landscape. As the dollar’s dominance faces structural pressure, Emerging Markets and Developing Economies (EMDEs) may become increasingly attractive from a diversification standpoint. The long-assumed stability of the U.S. financial system is now seen alongside growing debt concerns and policy uncertainty — underscoring the need for portfolio realignment.

Against this backdrop, transition investing has risen from the ashes of ESG as a compelling philosophy—one that mobilizes institutional capital, taps the catalytic dynamism of private markets, and delivers genuine investment additionality in the emerging and lower-income economies of the Global South, particularly across the Middle East, Africa, and South Asia (the MEASA region).

How can transition investing become the strategy of choice for large institutions, unlocking the essential reallocation of capital from developed markets to EMDEs? And in an era of rising sustainability backlash, how can investors not only survive but thrive—embracing change and building resilience against the shocks that will inevitably arise?

In this report, our readers will find some preliminary answers, grounded in data and rigorous economic reasoning.

The third edition of the Transition Investment Workshop (TIW) — at which this publication is officially launched — marks an important milestone for us. It builds on the success of TIW 2024 and reflects the growing visibility of the Transition Investment Lab (TIL) within the Abu Dhabi ecosystem over the past year, driven by multiple new initiatives, including a memorandum of understanding with the Global Climate Finance Center and a series of new strategic sponsorship agreements.

Collaboration is at the heart of TIL’s mission. Rather than advancing a single solution, TIL acts as a platform for dialogue and partnership — convening diverse stakeholders to explore how transition investment can deliver both competitive financial returns and meaningful social impact, while fostering sustainable, resilient economies that serve current and future generations.

Looking ahead, we will continue to deepen our research and analysis, and we invite you to follow our work as it evolves. We extend our sincere appreciation to our sponsors — Mubadala Investment Company and MEASA Partners — as well as to the TIL Steering Committee for their continued support. Finally, we are deeply grateful to our fellows and students, whose passion, dedication, and insights are central to advancing our research and impact.

Executive Summary

One of the key barriers preventing the mobilization of capital is the lack of reliable data on private equity investments in emerging markets. In their article, Arham Ahmed and Bernardo Bortolotti shed light on the issue by a comprehensive analysis of the role of multilateral banks and development financial institutions (DFIs) as limited partners in private equity funds.

Over the past 25 years, development finance institutions (DFIs) have committed about $40 billion to private equity — modest in global terms but often decisive in lower-income markets, where they are frequently the only investors willing to provide capital. In such contexts, DFIs act as anchor investors, de-risking funds, catalyzing co-investment, and enabling the growth of local private equity ecosystems. The data also reveal a structural shift, with a growing share of DFI commitments now directed toward advanced economies — a trend likely linked to domestic crisis responses and the push for sustainability and energy-transition investments. While aligned with policy priorities, this raises questions about the balance between domestic and international mandates. Going forward, key issues include how DFIs can mobilize more commercial capital in riskier markets, what collaborative models can scale their impact, and whether DFI-backed funds deliver competitive returns alongside development outcomes. However, progress on these fronts is hindered by persistent data gaps, particularly around deal values, performance, and disclosure. Addressing these shortcomings through collaborative data collection efforts is essential to evaluate DFIs’ effectiveness and foster private capital mobilization in EMDEs.

Sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) are increasingly pivotal to transition finance and sustainable investment. Their vast assets, growing strategic sophistication, and long-term, intergenerational horizons make them central to mobilizing capital at the scale required. Expectations of their role have also evolved: SWFs are now tasked not only with delivering financial returns but also with helping to address systemic global challenges. Chief among these is climate change, which for long-term investors is far from an abstract concern — it is a fundamental driver of portfolio risk, asset value preservation, and future investment opportunities.

In their article, Enrico Soddu and Abhinav Mangat fill a gap in the research about SWFs climate strategies, reporting data on their investments in the sector over a quarter of century to date. Climate-aligned investments have grown significantly since 2018, with annual commitments exceeding $20 billion and average ticket sizes reaching $158 million in 2024, converging to non-climate deal value. Interestingly, mitigation continues to account for the majority of cumulative allocations, reflecting the maturity of clean energy and efficiency technologies. However, adaptation is gaining traction, with $11 billion committed across 24 deals in 2024—surpassing mitigation in value. The increase appears to be driven by large-scale resilient infrastructure projects, where deal sizes are substantially higher than in mitigation. Importantly, the geographic distribution of SWF climate investments shows a persistent imbalance in capital flows and deal activity across income groups. Advanced and emerging economies have consistently attracted the bulk of these investments, while low-income developing countries (LICs) remain starkly underrepresented. The concentration of climate capital in developed markets highlights the need for risk-sharing mechanisms, including blended finance, to channel investment to the most vulnerable regions of the Global South, where resilience needs are greatest.

In a world defined by resource scarcity and mounting risks, adaptation and resilience—not just to climate change, but across the full spectrum of global challenges—are rapidly becoming a central focus for investors, policymakers, and businesses alike. Risk mitigation remains critically important. In today’s environment, capital must be allocated strategically to protect assets against a range of disruptions, from environmental shocks to technological upheaval, and mounting social risks.

According to Delilah Rothenberg, as technology accelerates global change, tackling economic inequality has become more urgent than ever. Addressing it requires synthesizing existing research, identifying gaps, and focusing on two key areas: understanding how companies and investors both influence and are influenced by inequality, and developing the tools to integrate these dynamics into decision-making. This includes new financial methodologies to price inequality-related risks and corporate accounting approaches that value human, social, and natural capital. Such tools can also support policymakers, regulators, ratings agencies, and communities in designing more equitable economic systems. Crucially, this effort must avoid a top-down approach and instead embrace co-creation with workers, communities, smaller enterprises, and disadvantaged regions. The multistakeholder governance model adopted by the Taskforce on Inequality and Social-related Financial Disclosures demonstrates how collaboration can shape context-specific solutions. Ultimately, addressing inequality demands a culture of systemic stewardship that transcends markets, aligning the actions of all stakeholders to confront the interconnected crises facing humanity and the planet.

One of TIL’s primary focus areas is the broad region comprising Middle East, Africa, and Southern Asia (MEASA). We firmly believe that the Global South is the region with the highest potential in terms of economic growth, but at the same time the least resilient to climate and social risks. For this reason, the report devotes a special section to the MEASA, with analyses covering each sub-region.

In his article, Neeshad Shafi points out that the MENA region, among the most climate-vulnerable in the world, is rapidly advancing carbon market initiatives as part of its broader transition to a low-carbon economy. Gulf countries, led by the UAE and Saudi Arabia, are developing comprehensive frameworks, including voluntary carbon markets, regulated exchanges, and Article 6 mechanisms under the Paris Agreement. The UAE has emerged as a pioneer with the region’s first regulated carbon credit exchange, a national carbon register, and policies integrating carbon credits into financial and tax systems. Saudi Arabia’s GCOM and RVCMC are driving large-scale voluntary credit auctions, while Egypt, Oman, Qatar, and Morocco are strengthening regulatory foundations and forging international partnerships. These developments are complemented by initiatives targeting compliance with CORSIA aviation offsets and proactive responses to EU carbon border measures. Looking ahead, carbon markets are poised to become a cornerstone of the region’s climate strategy, mobilizing private capital, accelerating clean technology, and supporting emissions reduction at scale. Coordinated regional frameworks and deeper engagement with Article 6 mechanisms could enhance policy alignment, boost investor confidence, and create a unified carbon trading bloc. By integrating robust regulation, financial incentives, and cross-border collaboration, MENA countries can play a pivotal role in shaping global carbon markets while advancing their own sustainability, diversification, and climate leadership goals.

Africa’s potential as an investment destination remains vast and largely untapped, yet the continent continues to present significant challenges from regulatory, structural, and market-access standpoints. Despite these hurdles, success stories are emerging that demonstrate how innovative approaches can unlock transformative growth. In her article, Nafisat Ahmed present the case of the Nigeria Sovereign Investment Authority (NSIA) — a powerful example of how a sovereign wealth fund can evolve beyond its traditional role as a savings and stabilization vehicle to become a catalyst for sustainable development.

Since its establishment, NSIA has combined disciplined financial management with a sustainability-driven mandate, investing over $500 million in domestic infrastructure, catalyzing $1 billion in third-party capital, and driving initiatives that span renewable energy, healthcare, housing, and financial market development. Its efforts have mobilized institutional investment, created platforms like InfraCredit and the Green Guarantee Company, and launched pioneering renewable energy projects and healthcare facilities, while supporting private equity growth across Africa. These interventions have generated over 300,000 jobs, unlocked more than $10 billion in economic activity, and enhanced Nigeria’s capital markets, all underpinned by strong governance and transparency. As Africa seeks to bridge its infrastructure gap and advance industrialization, NSIA offers a blueprint for how locally grounded sovereign wealth funds can attract global capital, deliver strong returns, and catalyse long-term, sustainable growth.

Last but not least, Robert W. van Zwieten offers an update on the latest trends shaping one of the most dynamic and rapidly evolving regions in sustainable finance. Southeast Asia is entering a pivotal phase in sustainable finance, moving from pilot initiatives to building the infrastructure needed to mobilize capital at scale. With nearly USD 1 trillion in ASEAN+3 sustainable bonds issued and rapid progress on taxonomies, disclosure standards, and carbon pricing, the region is laying the groundwork for large-scale transition finance. Yet challenges remain: project bankability, system-level risks, and credibility concerns—especially around sustainability-linked bonds—continue to deter investors. Overcoming these will require robust KPI enforcement, blended finance structures, and stronger regional integration, such as cross-border grid projects and interoperable carbon markets. If achieved, Southeast Asia could evolve from a destination for sustainable capital into a global model for transition finance, demonstrating how emerging markets can align policy, capital, and innovation to drive decarbonization and resilience.