1. Introduction

Over the past 25 years, sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) have evolved from specialized state-owned investors into influential participants in global financial markets. Today, they collectively manage more than $10 trillion in assets, shaping capital flows across asset classes and regions. Their investment decisions increasingly influence both market dynamics and the trajectory of climate and economic resilience. As their scale and sophistication have grown, so too has the expectation that these funds deploy capital in ways that not only deliver financial returns but also address systemic challenges. Climate change is foremost among these challenges. For long-term, intergenerational investors, climate change is not an abstract concern: it is a direct determinant of portfolio risk, asset value preservation, and future opportunity sets.

Within the climate-finance discourse, a central distinction has emerged between mitigation and adaptation. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) defines mitigation as interventions to reduce sources or enhance sinks of greenhouse gases. In contrast, adaptation refers to adjustments in ecological, social, or economic systems in response to actual or expected climate stimuli (IPCC, 2022). While mitigation has dominated the attention of policymakers, investors, and scholars alike, the urgent need for adaptation has become increasingly apparent. Despite the policy relevance of both strategies, capital flows remain heavily skewed toward mitigation, perpetuating an estimated $200 billion annual adaptation financing gap (UNEP, 2024). According to the Climate Policy Initiative (CPI) Global Landscape of Climate Finance 2024, less than 10% of total climate finance flows are directed toward adaptation, with the vast majority going to mitigation projects, particularly renewable energy, energy efficiency, and low-carbon transport (CPI, 2024). The UNEP Adaptation Gap Report 2024 underscores that adaptation finance is insufficient by a factor of five to ten compared to estimated needs, creating a persistent and widening shortfall (UNEP, 2024).

From a conceptual standpoint, the adaptation shortfall is puzzling. Indeed, adaptation projects typically target localized beneficiaries that would directly benefit from the enhanced resilience of their environment against climate-related events and associated damages. In contrast, mitigation benefits are truly global public goods, whose provision is affected by the usual free-rider and coordination problems. While all benefit from reduced emissions, individual countries often free-ride, undermining collective progress. The underinvestment in adaptation likely stems from its nascent market structure, challenges in monetising avoided losses, and the lack of proven financial instruments—rather than insufficient demand. Momentum is only now beginning to build as climate hazards are increasingly recognized as material financial risks. This persistent underallocation raises important questions about how long-term institutional investors, including sovereign wealth funds, can respond.

For sovereign wealth funds, these global patterns are particularly salient. Their mandates, whether to safeguard wealth for future generations, stabilise economies, or diversify national revenue streams, position them uniquely at the intersection of climate finance and public policy. As universal owners with long investment horizons, sovereign wealth funds are well-positioned to internalize global externalities such as climate change in their investment strategies. The IFSWF Annual Review 2024 noted a growing trend of adaptation-aligned investments in sovereign portfolios, which challenges the notion that sovereign wealth fund climate investments focus solely on renewables (IFSWF, 2024). Similarly, the IFSWF/One Planet Sovereign Wealth Funds (OPSWF) Climate Change Survey provided granular insights into how funds are incorporating both mitigation and adaptation considerations into their governance frameworks, investment processes, and disclosure practices (IFSWF–OPSWF, 2024).

In this article, we take a long-term perspective on sovereign wealth fund investment activity in response to climate change over the first quarter of the 21st century. Using a comprehensive dataset of sovereign wealth fund direct equity transactions, we address three key questions:

- To what extent have SWFs consistently pursued climate-related investment opportunities, and how has this evolved over time?

- How have SWFs balanced investments between adaptation and mitigation strategies, and how do these patterns compare with broader trends in climate finance?

- What future pathways could enable SWFs to scale adaptation investments while remaining aligned with their fiduciary duties and public mandates?

Some academic papers and policy reports have addressed broadly related questions. Liang and Renneboog (2020) have studied how SWFs incorporate environmental, social, and governance (ESG) considerations in their investment decisions in publicly listed corporations. Vaagenes Andersen, Wilts, Shan, Ruzzenenti, and Hubacek (2025) have examined the carbon implications of sovereign wealth fund allocations, highlighting the divergence between conventional and sustainable investment strategies in terms of global emissions outcomes. Bortolotti, Loss, and van Zwieten (2024) pioneered the tracking of sovereign wealth fund sustainability trends in the long run and identified a potential inflexion point in adaptation finance. However, no prior study has systematically compared adaptation and mitigation investments using transaction-level data over two decades.

Case studies of Singaporean sovereign investors GIC and Temasek illustrate how adaptation is being reconceptualised as an investable opportunity rather than merely a risk-management consideration. GIC’s report, “Sizing the Inevitable Investment Opportunity: Climate Adaptation,” estimated the adaptation market to be between $1 and $4 trillion in annual revenues by 2050, highlighting investable opportunities in sectors such as water resilience, urban cooling, and insurance analytics (GIC, 2025). Although the pool of investable opportunities may be smaller in the near term, the potential is significant. BCG and Temasek, in their report The Private Equity Opportunity in Climate Adaptation and Resilience, highlight projections from the 2024 UN Adaptation Gap Report that estimate annual financing needs for climate adaptation and resilience in the Global South at $215-387 billion between 2025 and 2030 (UN, 2024). When developed countries are included, the projected demand rises to $0.5-1.3 trillion annually by 2030. The report also mapped private-equity-style opportunities in adaptation and resilience, spanning climate intelligence, parametric insurance, resilient construction, and water reuse (BCG, Temasek, 2025).

At the same time, sovereign wealth funds such as Norway’s Government Pension Fund Global have continued to emphasise mitigation, particularly through unlisted renewables and stewardship activities across their listed portfolios. Norges Bank Investment Management (NBIM), which manages the fund, highlights the centrality of mitigation in its climate action plan and net-zero pathway (NBIM, 2024), while also beginning to acknowledge the materiality of physical climate risks. This tension between mitigation-heavy strategies and emerging adaptation opportunities captures the current state of play across the sovereign investment community.

Importantly, resilience research offers a conceptual bridge between climate science and investable adaptation categories. Systems-engineering literature highlights four functions of resilience: resist, restabilize, rebuild, and reconfigure (Gasser et al., 2019). These can be mapped to SWF-relevant adaptation investments: flood defenses and resilient materials (resist), backup power and water treatment (restabilize), climate-resilient reconstruction (rebuild), and adaptive urban design or digital infrastructure (reconfigure). Using this framework helps translate adaptation from an abstract policy term into a set of functional investment outcomes, aligning capital directly with resilience objectives.

2. Tracking Sovereign Wealth Fund Investments against Climate Change

This section draws on a proprietary dataset of over 5,000 sovereign wealth fund (SWF) direct investments from 2000 to 2024, compiled by the Transition Investment Lab (TIL) at NYU Abu Dhabi in collaboration with the International Forum of Sovereign Wealth Funds (IFSWF).

2.1 Harnessing the IRIS+ Taxonomy

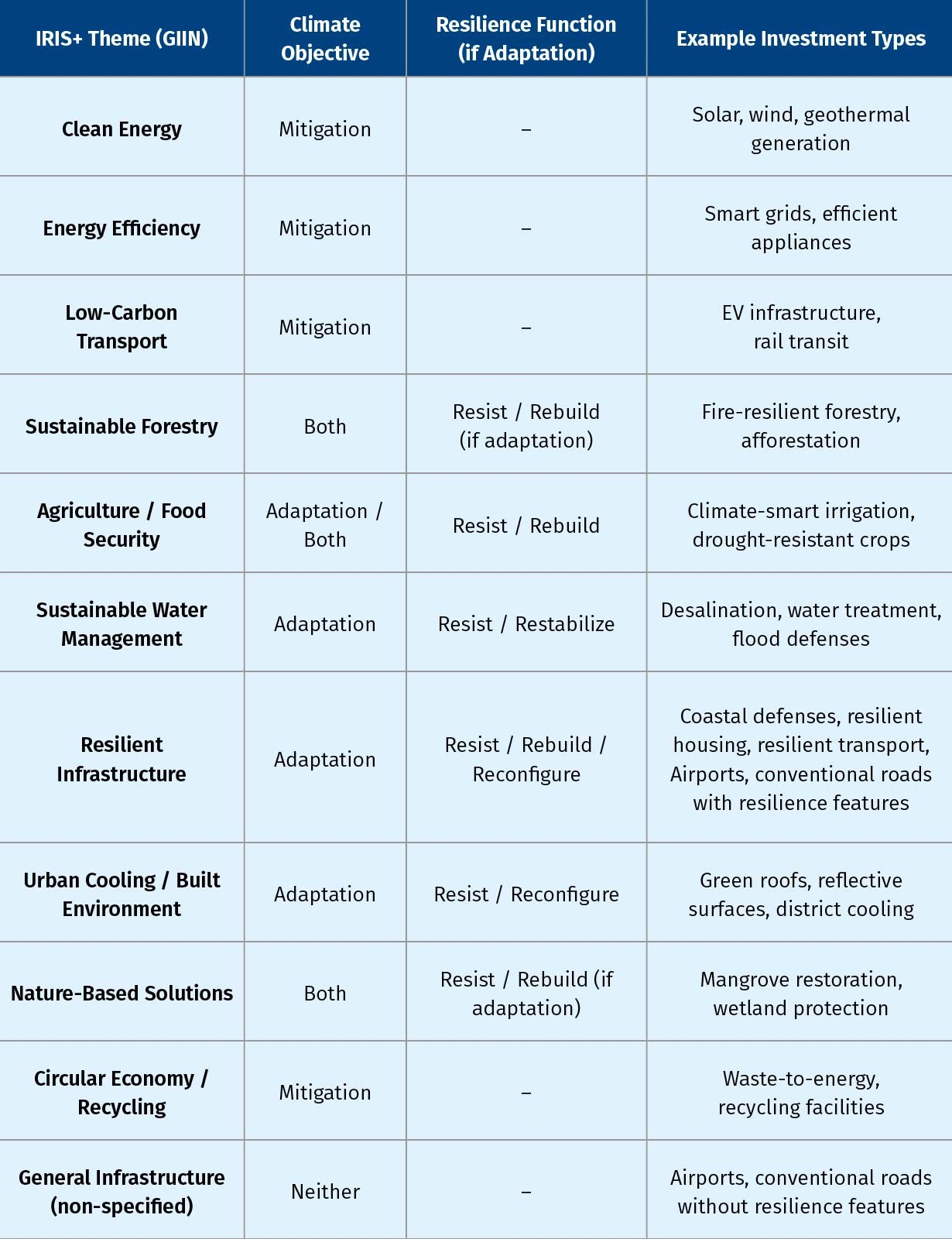

IRIS+ is the generally accepted system for impact measurement and management developed by the Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN, 2019-2024). It provides a standardized taxonomy of metrics, and guidance for integrating impact considerations into investment processes. While IRIS+ is designed to assess impact intentionality ex ante, TIL applied the framework ex post to tag and classify sovereign wealth fund direct investments in its database. While the original transactions weren’t structured with IRIS+ alignment, the framework serves as a useful benchmark for assessing sustainability and comparability. Each investment is tagged ex post to one or more IRIS+ categories and themes and mapped to climate objectives—mitigation, adaptation, both, or neither—based on internationally recognized frameworks such as those from the IPCC, OECD, and multilateral development banks.

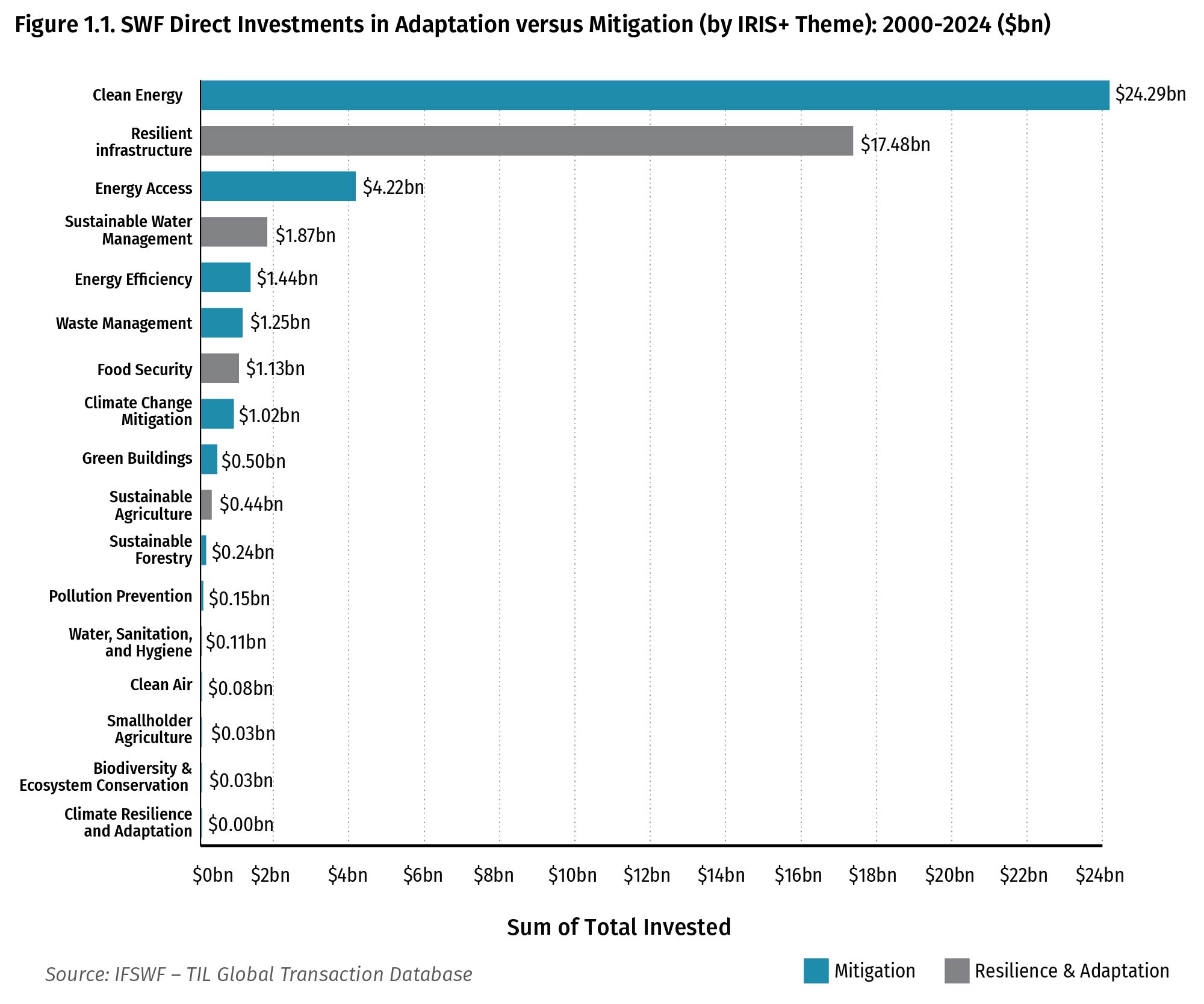

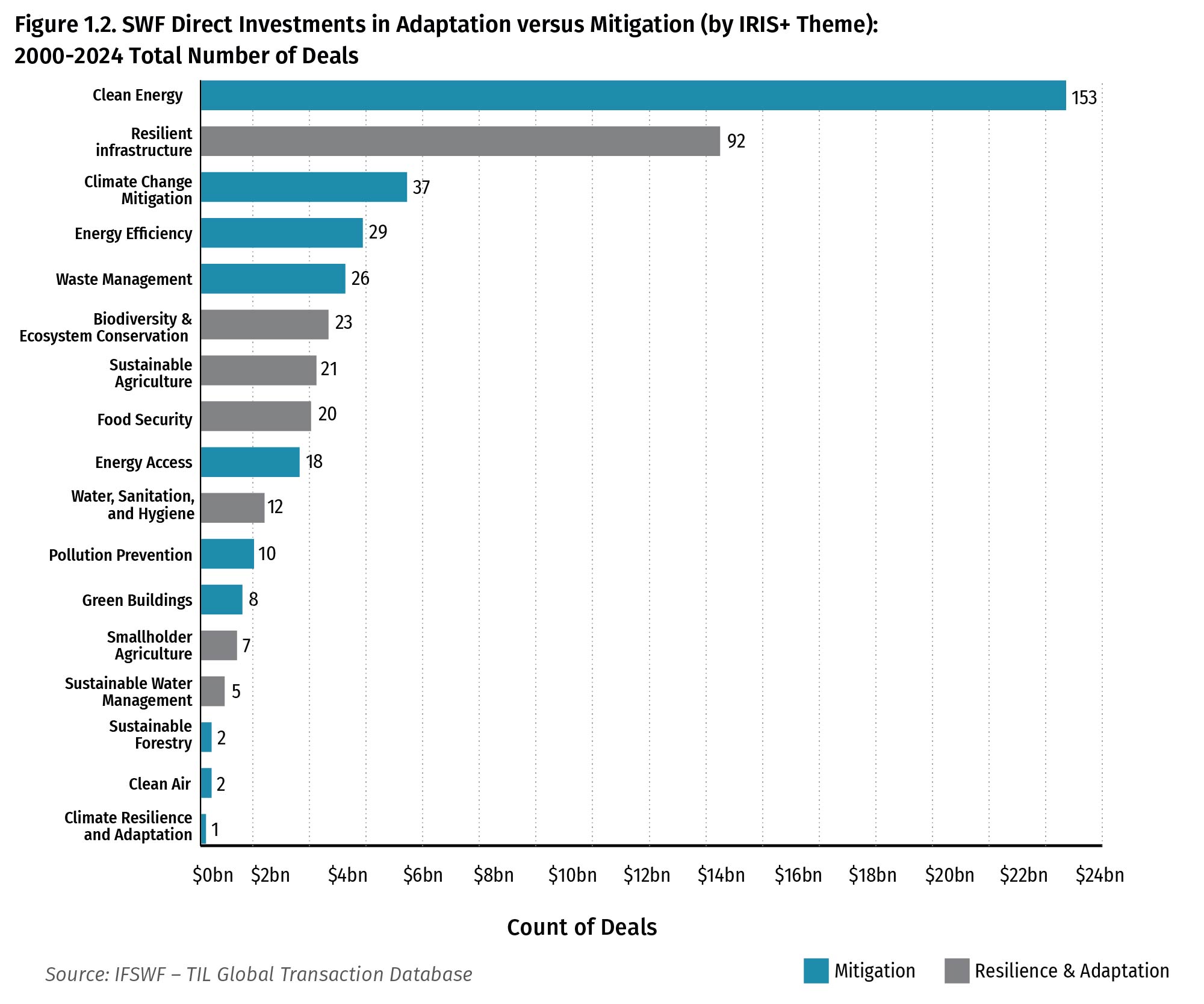

The data, spanning 25 years, reveal the SWF invested a total of $92 billion in 466 climate related deals, accounting for about 8 per cent of total investment value in the period. Clean energy leads with $24.3 billion across 153 deals, reflecting its central role in global decarbonization efforts. Resilient Infrastructure follows closely with $17.5 billion (92 deals), signaling growing recognition of climate-proofing critical assets. Adaptation-oriented themes such as Sustainable Water Management ($3.9 billion) and Food Security ($1.1 billion) attract comparatively smaller allocations, though their strategic importance is rising amid escalating climate risks. Notably, Energy Access ($4.2 billion) and Energy Efficiency ($1.4 billion) bridge both adaptation and mitigation objectives, indicating a trend toward integrated solutions. Lower-investment themes like Pollution Prevention and Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene suggest targeted interventions rather than large-scale capital deployment. Overall, the investment pattern underscores a strong mitigation bias, but adaptation-related funding is gradually gaining traction, aligning with the increasing urgency of climate resilience.

2.2 Temporal Dynamics and Scaling Patterns

This section traces how SWFs in climate themes evolved across market cycles, with shifting strategic priorities and deal characteristics.

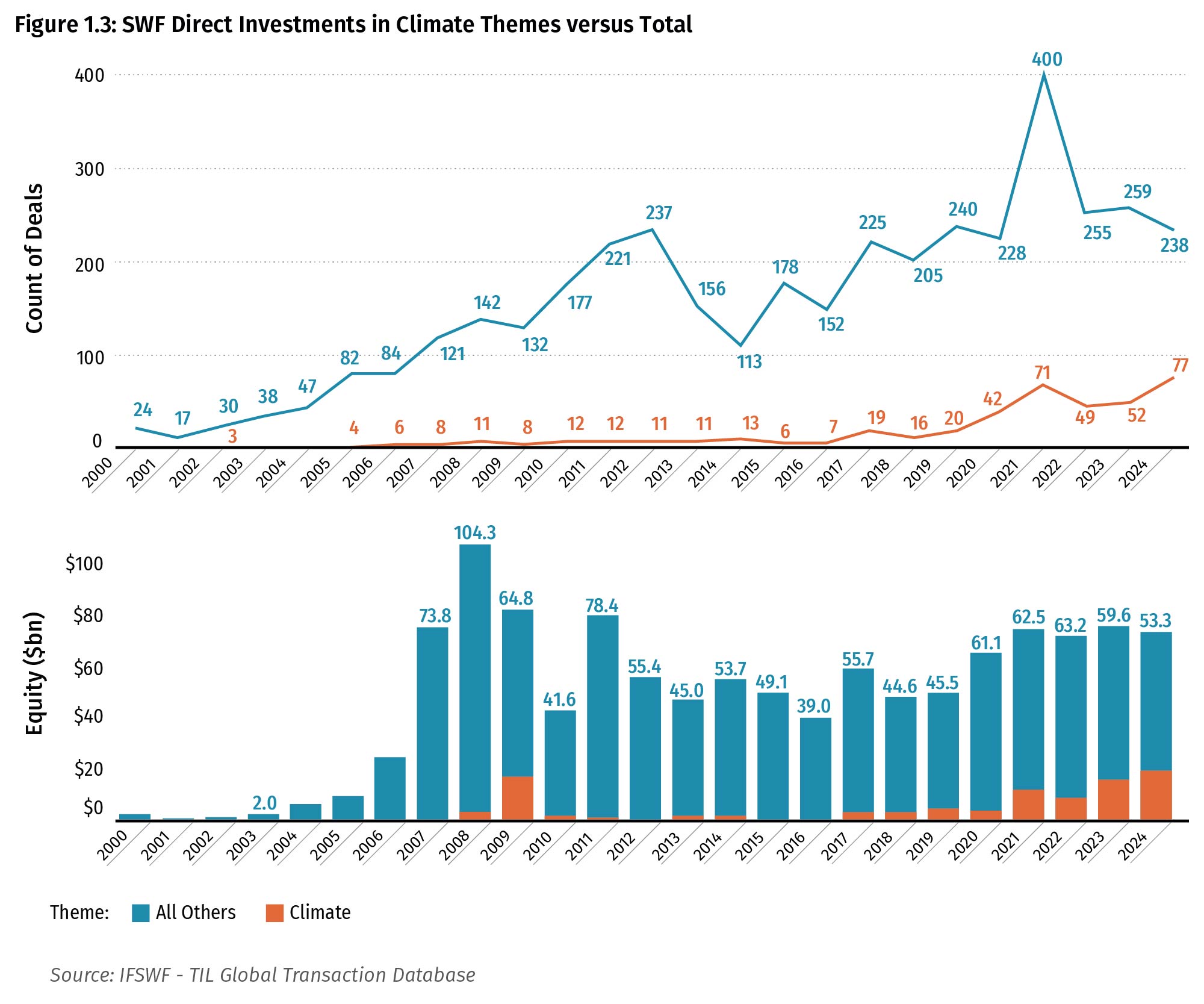

From 2000 to 2008, using the IRIS+ lens, investments in climate adaptation and mitigation represented less than 2% share of sovereign wealth fund direct investments. Deal counts rarely exceeded single digits annually, and value allocations were minimal compared to the total invested. This early phase was marked by cautious experimentation rather than mainstream adoption.

Following the 2008 global financial crisis, sovereign wealth funds entered a reactive investment cycle. They stepped in to stabilise financial institutions and acquired distressed assets, particularly in banking and financial services. Between 2009 and 2012, deal volumes surged as sovereigns stabilized institutions and pursued energy and infrastructure assets, though average ticket sizes remained modest.

Between 2016 and 2019, the fading of the commodities boom, rising geopolitical uncertainty, and slower global growth led many sovereign funds to adopt a more cautious posture. Direct investments became more selective, and allocations shifted toward diversification and risk management. This phase reflected strategic restraint rather than expansion.

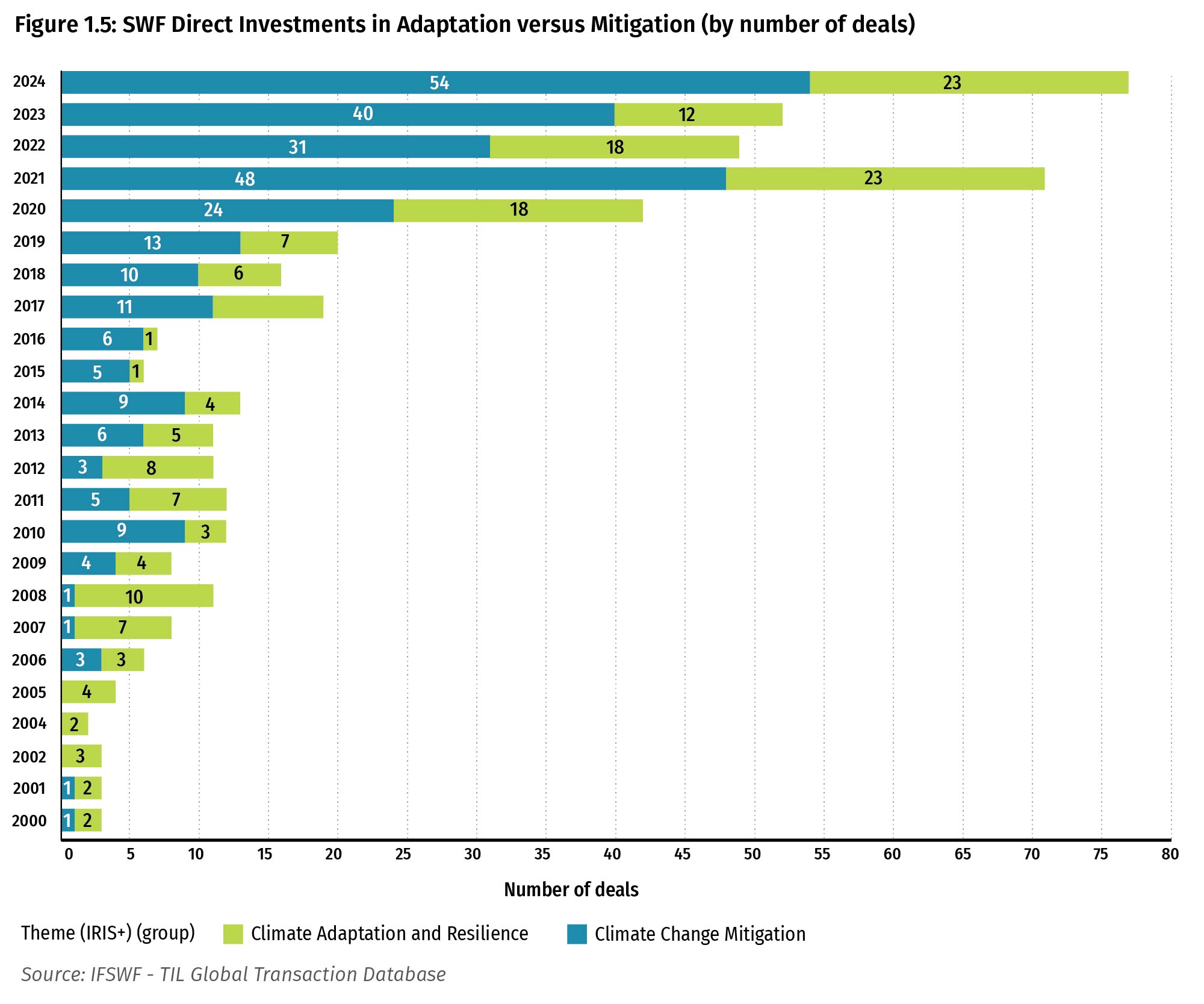

The picture changed dramatically after 2020. As illustrated in Figure 1.3, investments in climate accounted for 42 deals out of 270 total in 2020 (15.6% by volume) and about $3 billion out of $61.9 billion in SWF direct investments (4.8% by value). By 2024, these shares had surged: 77 deals out of 315 (24.4% by volume) and $10.6 billion out of $63.2 billion (16.8% by value). This represents a 57% increase in total deal share and a 3.5x increase in value share in just four years (see Figure 1.3), signaling a structural shift toward climate-aligned strategies. The COVID-19 crisis accelerated sustainability integration as non-financial risks—public health, supply chains, social cohesion, and climate—proved material to long-term returns.

Within investments in climate, mitigation themes dominate—Clean Energy ($24.3 billion across 153 deals) and Resilient Infrastructure ($17.5 billion across 92 deals) lead the pack—while adaptation-oriented areas such as Sustainable Water Management ($3.9 billion) and Food Security ($1.1 billion) remain underrepresented but strategically critical. These figures echo the thematic composition discussed earlier.

This recent phase is distinguished by both a rebound in activity and larger transaction sizes. Average ticket size rose from ~$122 m in 2021 to ~$158 m in 2024. This indicates growth is driven by larger, infrastructure-intensive deals rather than more numerous small ones.This pattern contrasts with the earlier peak in 2009–2012, when deal volumes surged but average sizes remained comparatively modest.

Since 2022, investment strategies have shifted from COVID-19 stimulus toward a more constrained climate marked by geopolitical instability and recurring shocks. Yet, unlike previous cycles, sustainability-aligned strategies are not retreating, but now occupy a stable and growing share of institutional portfolios. The shift toward larger ticket sizes and longer holding periods—particularly in energy transition and resilient infrastructure—signals a deeper institutionalisation of climate themes. Investors now treat sustainability as a strategic anchor for long-duration capital, not a tactical overlay.

2.3 Adaptation and Mitigation: Framing the Sovereign Investment Landscape

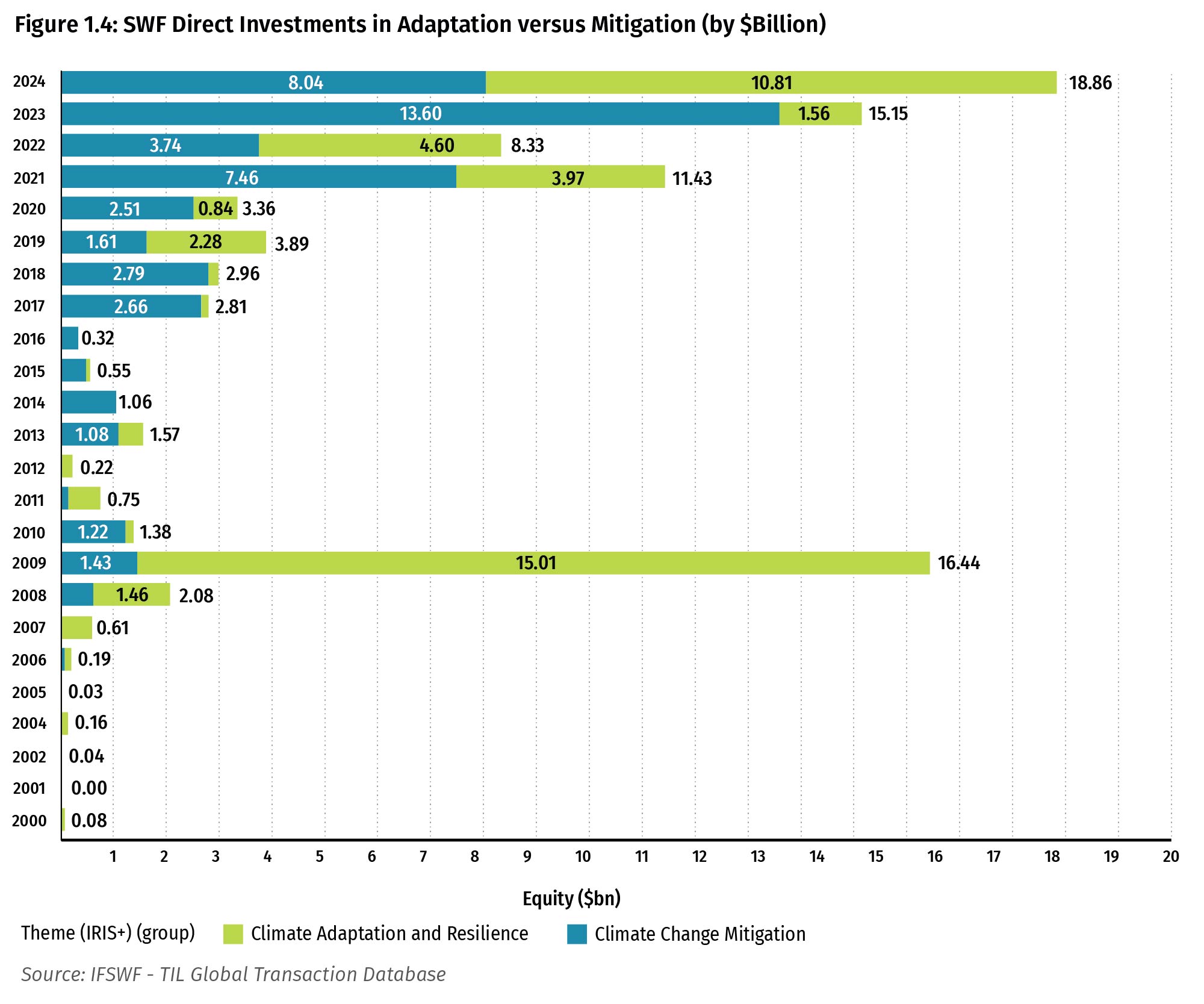

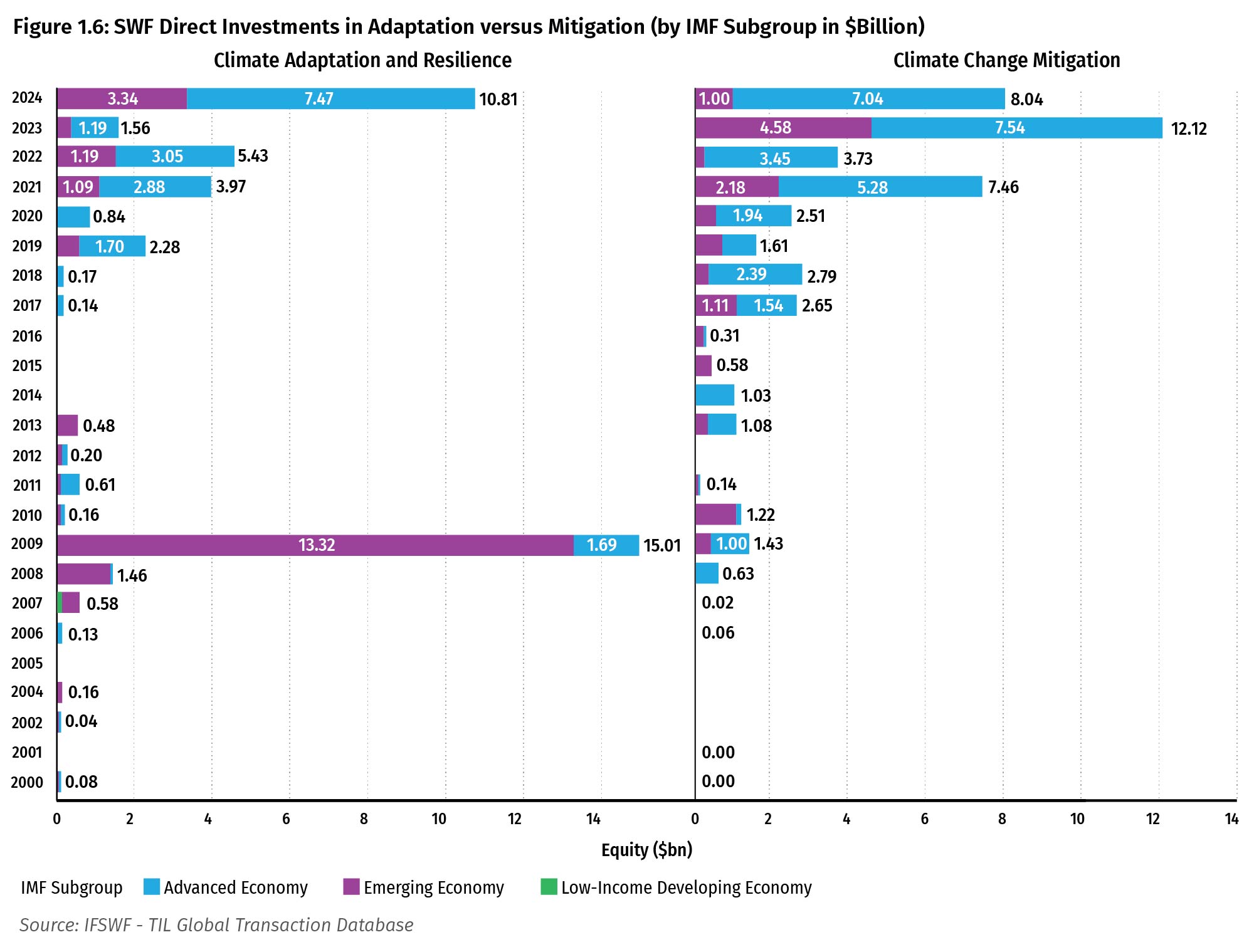

Notably, the data is skewed by a 2009 outlier, when the Qatar Investment Authority (QIA) fast-tracked Qatar Railways under Qatari Diar – a move signaling a strategic pivot toward climate-resilient urban infrastructure, anticipating rapid population growth and Gulf heat stress.

This was one of the earliest and largest sovereign-led adaptation plays, predating institutional mainstreaming by nearly a decade. The decision reflected a convergence of national resilience priorities and long-horizon capital deployment strategies, positioning QIA as a first mover in embedding adaptation into core infrastructure planning.

Mitigation still dominates cumulatively, but adaptation gained ground in 2024—surpassing mitigation in value despite fewer deals. This pattern aligns with the IFSWF Review’s suggestion that adaptation may surpass mitigation in some years. It also reflects the shift noted in the introduction, as leading funds expand focus from decarbonisation to resilience.

This shift becomes clearer when climate objectives are mapped to IRIS+ themes. Clean energy and energy efficiency dominate mitigation due to their maturity and scalability. A pivotal moment came in 2006 when Mubadala Investment Company launched Masdar, a dedicated clean energy platform. Masdar’s creation institutionalised climate investing at scale, deploying nearly $30 billion across 40 countries and becoming a reference point for sovereign-led decarbonisation (Masdar Factsheet, 2024).

Recent mitigation investments continue this trajectory. In 2024, Temasek co-led a €145 million round in Aira, a European heat pump firm aiming to replace fossil-fuel boilers and reduce residential CO₂ emissions. The Oman Investment Authority recently backed Hysata, an Australian green hydrogen firm developing high-efficiency electrolysers. These examples reflect the IRIS+ classification of mitigation-aligned investments under themes such as renewable energy, energy efficiency, and clean industrial processes.

In adaptation, resilient infrastructure has emerged as the principal conduit for capital, followed by sustainable water management and food security. The 2009 Doha Metro investment remains a landmark, but recent deals show growing momentum. For example, the National Investment and Infrastructure Fund (NIIF) invested $200 million in iBUS Network to expand climate-adapted digital infrastructure in India. Food security and resilience in agriculture are quickly rising as hotspots, too. In 2024, for example, Mubadala committed $4.2 billion to Australia’s Perdaman Urea Project, designed to support 90 million people while integrating low-carbon technologies. The Angola Sovereign Wealth Fund (FSDEA) committed $10 million to the Cabinda Phosphate Fertiliser Project, targeting drought-resilient agricultural inputs.

The IRIS+ framework categorises these investments under climate resilience, sustainable agriculture, and adaptive infrastructure.

2.4 Geographic Distribution and Investment Gaps in Low-Income Countries

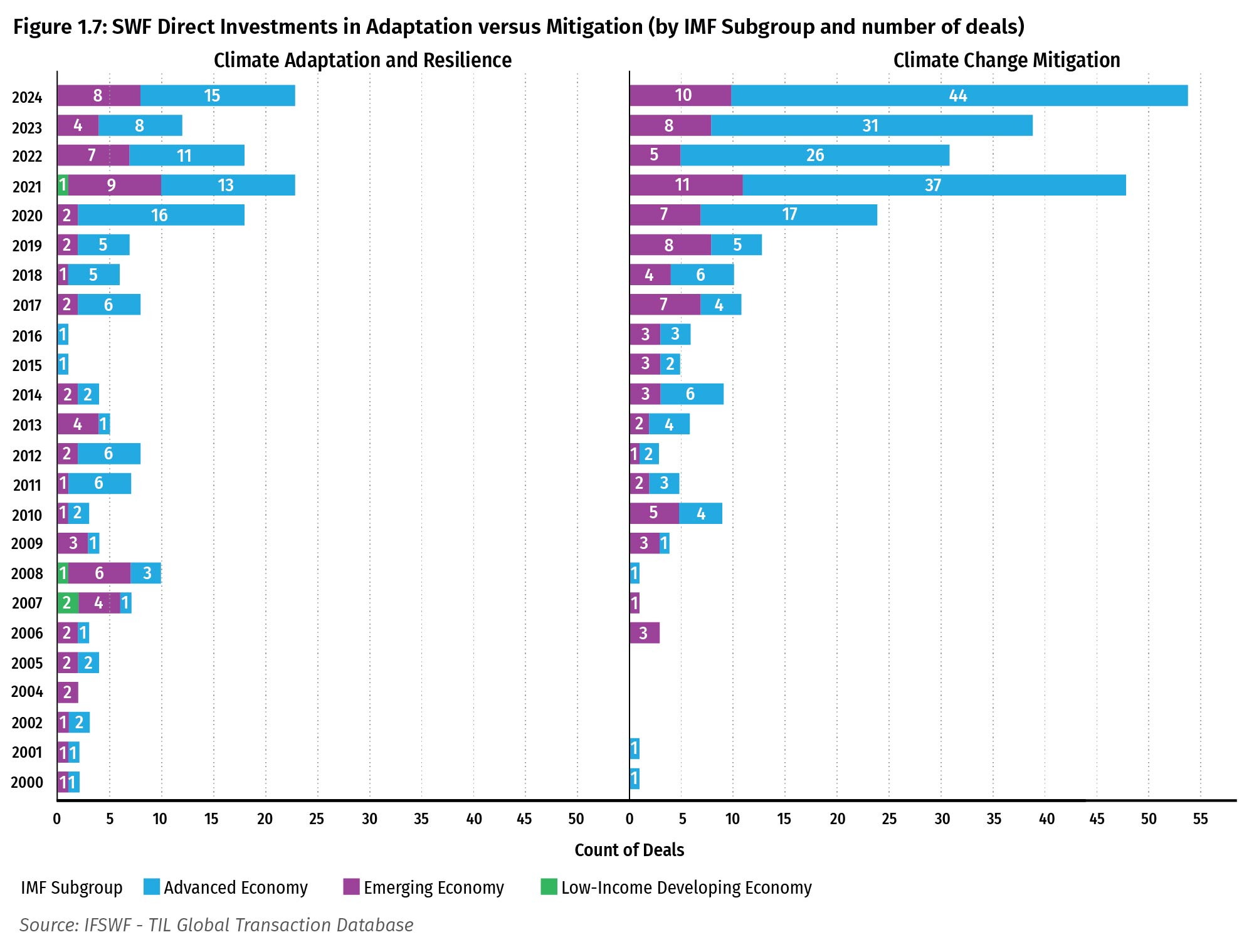

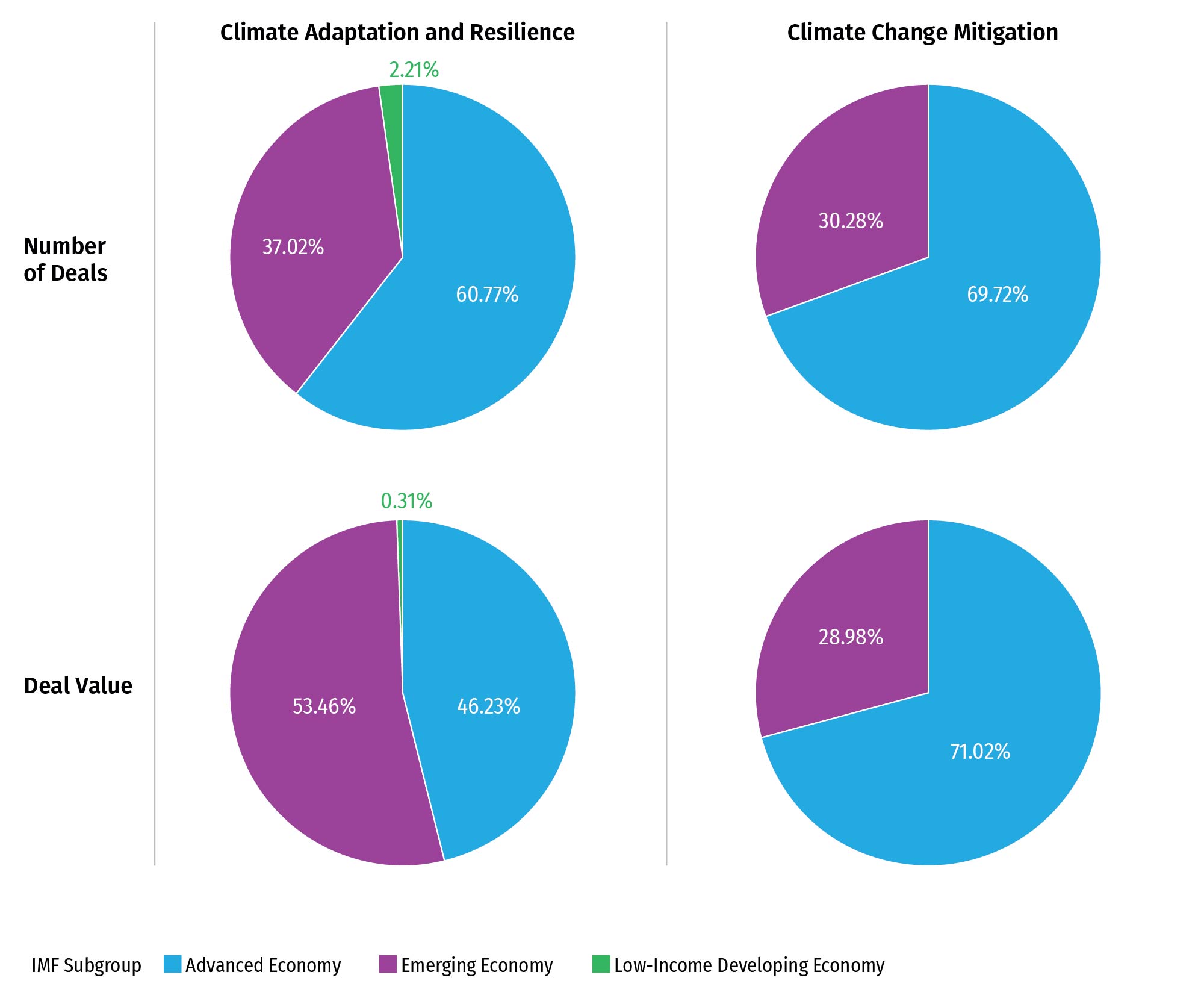

Between 2000 and 2024, the geographic distribution of sovereign wealth fund (SWF) climate investments reveals a persistent imbalance in capital flows and deal activity across income groups. Advanced economies have consistently captured the majority of this capital, accounting for 61% of adaptation and 70% of mitigation investments, respectively.

The distribution of investments by deal value presents a slightly different picture. While the majority of mitigation capital still flows to advanced economies, emerging markets accounted for 53% of total deal value, largely driven by a single outsized infrastructure transaction by QIA previously identified as an outlier. Even so, recent data indicate that investment in climate resilience across emerging markets is beginning to gain momentum.

It is encouraging to see sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) increasingly supporting resilience initiatives in more vulnerable regions. However, a deeply concerning trend is the complete absence of investment in low-income countries (LICs). Over the entire 25-year period, only three deals were recorded in LICs — one each in 2007, 2008, and 2021 — all focused on agriculture or land-based adaptation. Their limited scale and sporadic nature stand in stark contrast to the sustained and growing activity in higher-income economies. This pattern highlights a widening adaptation finance gap precisely where vulnerability is greatest, underscoring the urgent need for sovereign investors to adopt a more catalytic role in mobilising capital for climate resilience in the world’s most exposed regions.

In mitigation, the imbalance is even more pronounced, with LICs receiving zero deals throughout the entire period. However, this pattern is not necessarily unexpected. Clean energy investments—such as solar farms, wind infrastructure, and grid modernization—are capital-intensive and often concentrated in advanced economies due to their technological readiness, regulatory frameworks, and market stability. LICs, by contrast, face structural constraints that limit their ability to invest in mitigation technologies. These countries often lack basic infrastructure, stable energy access, and sufficient fiscal space. For many, the priority is not decarbonization but survival—ensuring food security, access to clean water, and protection from climate-induced disasters. Expecting LICs to invest in mitigation before meeting basic needs risks perpetuating a free-rider dynamic—wealthier nations benefit, while poorer countries face climate impacts without the means to respond.

This underscores the importance of directing climate finance toward adaptation in LICs, where the returns are measured not in carbon offsets but in lives protected and systems strengthened. Reports from the IMF and World Bank have long emphasized this misalignment. The IMF’s Fiscal Monitor: Climate Crossroads – Fiscal Policies in a Warming World (2023) and the World Bank’s People in a Changing Climate: From Vulnerability to Action (2024) both stress the urgent need to redirect climate finance toward vulnerable low-income countries. Figure 1.6 confirms this persistent marginalization: after two decades, LICs remain excluded from SWF climate finance—both in capital flows and deal activity.

Conclusion

The analysis in this report suggests that sovereign wealth funds are shifting from a mitigation-dominated approach toward a more balanced strategy that incorporates adaptation as a significant investment theme. Climate-aligned investments have grown significantly since 2018, with annual commitments exceeding $20 billion and average ticket sizes reaching $158 million in 2024. This indicates that climate objectives are now embedded in the majority of SWF governance frameworks.

Mitigation continues to account for the majority of cumulative allocations, reflecting the maturity of clean energy and efficiency technologies. However, adaptation is gaining traction, with $11 billion committed across 24 deals in 2024—surpassing mitigation in value. The increase appears to be driven by large-scale resilient infrastructure projects, where deal sizes are substantially higher than in mitigation. Findings suggest a structural shift, but interpretation requires caution due to data limitations and classification caveats outlined earlier.

Three priorities emerge for scaling sovereign climate investment. First, the concentration of climate capital in developed markets highlights the need for risk-sharing mechanisms to channel investment toward emerging and frontier economies, where resilience needs are greatest. Second, the development and consolidation of robust data-driven de-risking tools—such as credit performance datasets and scenario-based stress testing—will be essential to validate climate investments within commercial mandates. Third, harmonized taxonomies and disclosure standards remain critical for converting climate ambition into investable pipelines—a prerequisite for mobilizing long-term sovereign capital toward global climate goals.

Appendix: Classification of Investments by Climate Objective

Methodology

This article employs a longitudinal analysis of sovereign wealth fund (SWF) direct investments from 2000 to 2024 to assess how sovereign investors have engaged with the dual objectives of climate mitigation and adaptation. The methodological design builds upon our earlier work for the IFSWF Annual Review 2024 and the IFSWF-OPSWF Climate Change Survey, but extends the scope by leveraging the unique dataset of the Transition Investment Lab (TIL) at New York University Abu Dhabi, which contains over 5,000 SWF direct investments spanning more than two decades.

Classification framework

To classify investments, we developed a dual-layer tagging system:

- First layer (IRIS+ Taxonomy, GIIN): Each investment is mapped to one or more IRIS+ themes, such as Clean Energy, Sustainable Water Management, or Resilient Infrastructure.

- Second layer (Climate Objective Mapping, MDB/IPCC/OECD frameworks): Each theme is then assigned to a climate objective—mitigation, adaptation, both, or neither—based on internationally recognized definitions. For example, Clean Energy and Energy Efficiency are mitigation; Resilient Infrastructure and Food Security are adaptation; and themes like Sustainable Forestry may count as both.

In addition, we overlay insights from resilience literature, which disaggregates adaptation into four functional categories: resist, restabilize, rebuild, and reconfigure (Gasser et al., 2019). These functions are applied as a supplementary coding layer to adaptation-aligned deals, enabling us to distinguish between investments that harden systems against shocks (resist), support rapid recovery (restabilize), finance reconstruction (rebuild), or redesign systems for long-term resilience (reconfigure).

This overlay methodology was first piloted during the IFSWF Annual Review 2024 and is here applied consistently across the full TIL dataset.

Quality assurance

Initial classification is produced through a combination of keyword-based scripts and supervised learning models trained on a validated subset of deals. Ambiguous cases—such as agricultural investments that may contain both mitigation and adaptation features—are resolved through expert review and manual adjudication, following the protocols established during the 2024 Review.

Data Limitations and Interpretation Caveats

The findings presented in this report should be interpreted with caution due to several limitations inherent in the dataset. The database has been compiled and enriched over multiple phases by different research teams, which means that variations in inclusion criteria, classification practices, and verification standards may affect comparability across time. In addition, the IRIS+ taxonomy was applied retrospectively to historical transactions. This ex post mapping does not imply that the original investments were structured with an explicit impact objective; therefore, thematic classifications should be understood as indicative rather than definitive.

Coverage is another important consideration. Earlier periods may be underrepresented in certain themes or geographies due to limited disclosure or differences in data capture priorities, while more recent years may appear disproportionately active due to improved reporting and coding granularity. Finally, differences in interpretation or emphasis by successive research teams could have influenced how borderline cases were categorised, particularly in emerging thematic areas.

Taken together, these factors mean that observed patterns such as apparent cycles or structural shifts may reflect, in part, changes in data collection and coding practices rather than purely underlying market dynamics. Readers are encouraged to interpret long‑term trends with these caveats in mind.