1. Introduction: Inequality Takes the Stage Alongside Climate and Nature Risks

Climate change and biodiversity loss are increasingly recognized as systemic risks to companies, financial markets, and investors’ diversified portfolios. This is reflected in a multitude of initiatives and commitments by companies, investors, policymakers, regulators, and other organizations seeking to address these risks – from the Taskforce on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) launched by the G20’s Financial Stability Board (FSB), to the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) comprised of central banks and financial supervisors, to the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ) and Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD) with the support of financial institutions representing trillions of dollars.

Inequality and social-related risks are beginning to receive comparable attention. The emerging Taskforce on Inequality and Social-related Financial Disclosures (TISFD) is laying the conceptual foundations for a disclosure framework that is anticipated to support companies and investors in understanding their relationships with inequality and social risk – particularly how they might contribute to or alleviate these risks, and how they are affected by them.

Some of the world’s most influential financial figures have warned that growing economic inequality poses a threat not only to society but to capitalism itself. Ray Dalio of Bridgewater Associates, Bill Ackman of Pershing Square, Jerome Powell of the Federal Reserve, and Janet Yellen of both the US Treasury and Federal Reserve have all identified economic inequality as a critical risk. These individuals are from the world’s largest capital market – the U.S. – and their views reflect perspectives across the political spectrum. It is telling that even those who have benefitted most from the current system recognize that unchecked inequality can ultimately undermine it.

These perspectives are complemented by those of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), United Nations (UN), and World Bank, which have repeatedly highlighted the destabilizing effects of inequality within and between countries at various points in time. As outlined below, economic inequality can lead to social unrest, inhibit progress on climate and nature goals, and exacerbate what has come to be known as the broader “polycrisis.” It can also destabilize financial markets by concentrating wealth and power across individuals, firms, and regions, as well as through effects on price stability and interest rates, thereby contributing to asset bubbles and credit crises.

While the academic and policy literature on these issues is vast, it is also scattered and has yet to be curated and synthesized in ways that inform the private sector decision-making. Until TISFD, there has been no concerted effort by the financial services industry to understand inequality as a systemic risk – its origins, mechanisms, and potential remedies.

There has been progress in the field of business and human rights as reflected in the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs) and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Guidelines for Multinational Corporations, as well as frameworks with a focus on certain stakeholder groups, such as the International Labour Organisation (ILO) standards or those developed to address gender or economic development in undercapitalized regions. However, there has been no comprehensive “Stern Review” or “Dasgupta Review” for economic inequality that speaks to the complexities of how it manifests across workers, communities, consumers, value chains, geographies, market structure, and other dimensions.

As a founding member and current Steering Committee member of TISFD participating in its development since the beginning, I have seen how the systemic risks of inequality to financial markets remain less understood than those of climate and nature, even as they may prove more immediate and act as a barrier to addressing other facets of the polycrisis. In this article, I share my own reflections and learnings on these emerging risks, as well as perspectives on what is needed by the market to understand and adequately address them. These reflections are not intended to represent the views of TISFD.

2. Understanding Inequality and Social Risks

TISFD emerged in 2023 through the convergence of two earlier initiatives: the Taskforce on Social-related Financial Disclosures (TSFD) and the Taskforce on Inequality-related Financial Disclosures (TIFD). As these initiatives joined forces, the question arose as to the relationship between social versus inequality-related risks. Is one a subset of the other? This is not for any one individual or institution to determine, and some level of consensus is anticipated to emerge as the TISFD framework develops with input from stakeholders across the investment, business, labor, civil society, and academic communities.

Perhaps of more immediate concern, when developing financial disclosures, it is critical to understand how the resulting framework speaks to the concept of financial materiality. According to the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) of the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS),

“Information is material if omitting, misstating, or obscuring it could reasonably be expected to influence investor decisions,” further noting that, “IFRS… asks for disclosure of information about sustainability related risks and opportunities to meet investor information needs. That means information about all sustainability-related risks and opportunities that could reasonably be expected to affect the company’s prospects – its cash flows, access to finance or cost of capital over the short, medium, or long term.”

Financial materiality (sometimes referred to as “single financial materiality”) traditionally refers to issues which may financially impact the performance of a company or security in a material way.

Yet another conception of materiality is impact materiality, which refers to issues that may impact and be salient to corporate stakeholders (people) such as workers, supply chain actors, communities, and consumers. When both impact materiality and financial materiality are considered together, this is known as double materiality.

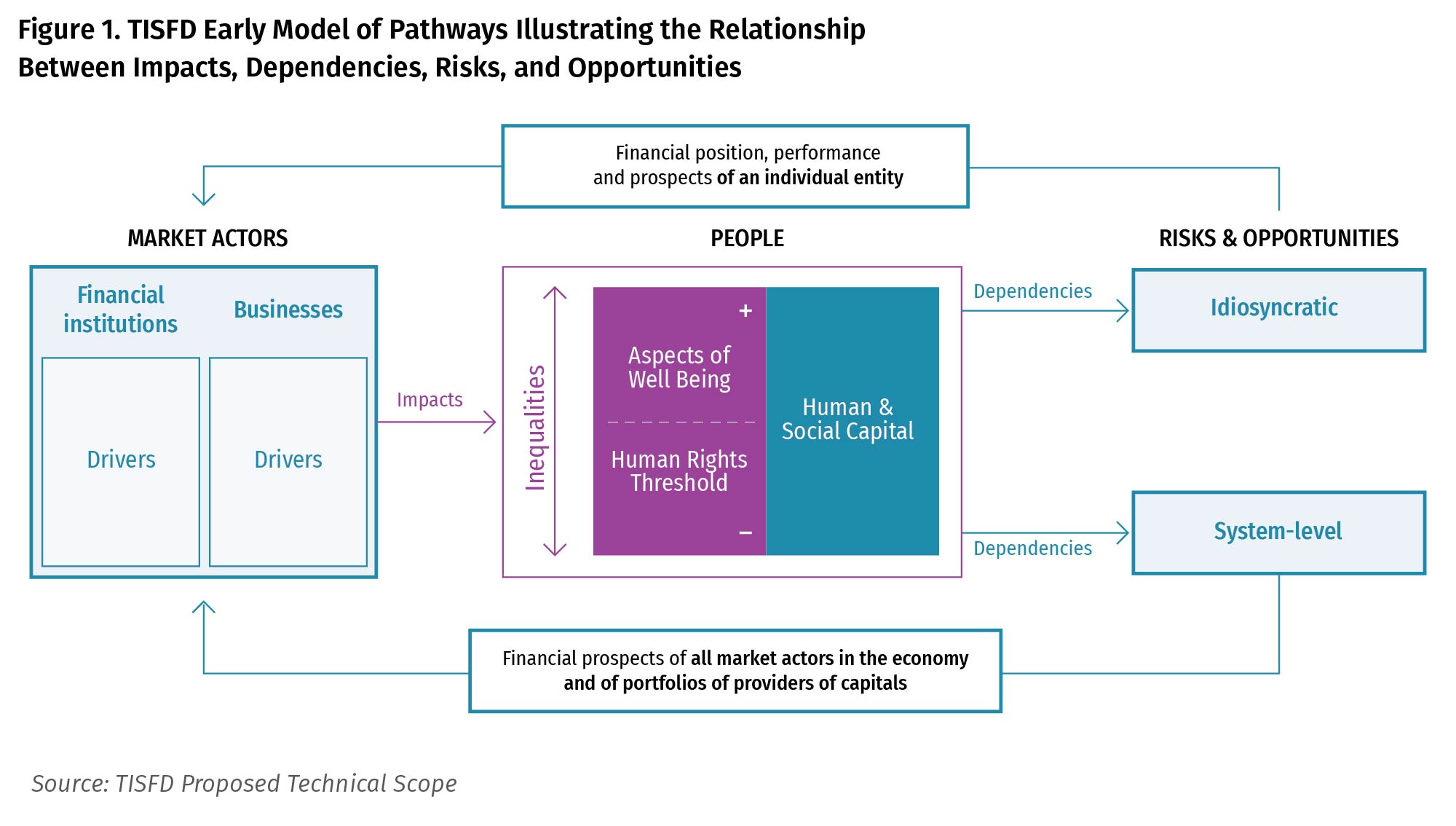

The relationship between financial and impact materiality can be understood through the concept of Impacts, Dependencies, Risks, and Opportunities (IDROs), often applied in the context of nature risks. A company may contribute to negative impacts that exacerbate nature loss – for example, soil degradation from intensive farming or depletion of marine life through over-fishing. Yet this same company is also dependent on healthy ecosystems to enable it to sustain operations and continue as a going concern; healthy soil will be needed to grow crops in the future, and fish stocks must be replenished to maintain catches. In this sense, soil and fish function as forms of natural capital, akin to financial capital, that take on risk and create financial value within a transaction or production process. Viewed through the lens of these dependencies, the deterioration of natural capital becomes a financially material risk to a company. Conversely, financially material opportunities can arise when companies adopt practices such as regenerative farming and fishing that enable the replenishment of natural capital even as it is used, securing both environmental and economic resilience.

In the context of social risks, companies are generally dependent on workers and the supply chain (human capital) and communities and consumers (social capital) to thrive. It is often said by senior executives that “people are our greatest asset,” thereby indicating they create material financial value. Further, numerous studies demonstrate that corporate success is dependent on a social license to operate, implying the financial value from communities and consumers.

While some may argue that with the growth of artificial intelligence (AI) and automation, companies will be able to reduce their dependencies on workers, it is imperative to consider that workers are also consumers who keep economies functioning. If workers do not have robust incomes, this will eventually impact companies’ consumer bases and threaten the overall economy, thereby creating a negative feedback loop that can materially affect corporate financial performance in the future. These “systemic” dependencies are described further below.

When a company’s impacts do not clearly translate into financially material risks or opportunities for that company over the short, medium, or long-term, those impacts become economic externalities. In the case of negative impacts, these externalities are costs that someone or groups other than the company must bear. Negative externalities – such as from payment below a living wage to workers or the accumulation of greenhouse gas emissions – can accumulate to become systemic risks to human and natural systems. Because well-functioning economies depend on the stability of these underlying systems, and well-functioning financial markets depend on economies, these negative externalities can pose systemic financial risks to financial markets and therefore investors’ diversified portfolios.

As argued by Jon Lukomnik and Jim Hawley in their book, Moving Beyond Modern Portfolio Theory: Investing that Matters, and Keith Johnson, Tiffany Reeves, and colleagues across several key works, externalities and the resulting systemic financial market risks are especially significant to large, long-term, diversified investors with intergenerational fiduciary duties, such as pension funds and often sovereign wealth funds. Because their portfolios are so diversified, they are exposed to nearly every industry, geography, and asset class and cannot diversify away systemic risks arising from the accumulation of externalities. Lukomnik and Hawley note, “more than 75 percent of the variability in the return to an investor is caused by systematic risk – that is, some combination of beta and how much exposure an investor has to that beta.” In this way, systemic risks to human, natural and economic systems become systemic and systematic risks (collectively referred to throughout the rest of this article as systemic risks for simplicity) to financial markets and diversified portfolios, and potentially to individual companies, as well.

Thus, even if a climate, nature, or inequality-related impact is not linked to a material dependency of an individual company—and thus does not lead to material financial risk to that company—the accumulation of such impacts as externalities materially affect the dependencies, risks, and opportunities of financial markets and diversified investors. So IDROs can be understood across two dimensions:

- The idiosyncratic level for a given company or security, and

- The systemic systemic-level for an investment portfolio.

Arguably, these two dimensions overlap. Much of the impact on diversified portfolios will manifest through the aggregate performance of portfolio companies, although not exclusively. Financial portfolios also comprise of non-corporate assets such as commodities, currency, and sovereign and sub-sovereign debt that are influenced by macro-level, non-linear dynamics and feedback loops, including shifts in interest rates and broader economic conditions.

3. Various facets of inequality

Before examining how inequality can create systemic risk, it is important to clarify what is meant by inequality in this context. In the report, “The Investor Case for Fighting Inequality: How Inequality Harms Investors and What They Can Do About It,” various definitions of socioeconomic inequality (referred to as “economic inequality” in this article) are summarized. Together, the UN Development Programme (UNDP) and the OECD describe it as disparities in income, wealth, living standards, capabilities, and access to opportunities such as education, healthcare, employment, and social mobility. They also reference intergenerational inequality, which involves “the transmission of socioeconomic advantages or disadvantages from one generation to the next, affecting long-term development prospects.”

Inequality is often understood across two dimensions: vertical and horizontal. As explained by the Fairness Foundation, “Vertical inequalities are inequalities between individuals or households, such as income or health inequalities… Horizontal inequalities are inequalities between groups, such as people of different genders or ethnicities.”

In many ways, horizontal inequality stems from cultural and historical factors which have systematically undervalued certain populations and put them at a disadvantage when it comes to access to resources, wealth, and societal influence. These inequities are reflected in patterns of discrimination and unequal opportunity. As markets evolved around dominant definitions of economic productivity and growth – set largely by those who have wealth and influence – certain forms of physical and cognitive ability have also been privileged over others. These various forms of discrimination not only affect wealth-building and social advancement opportunity of the present generation, but also the prospects of future generations. Intergenerational disadvantages can compound through access to education, health and wellbeing, inheritance, and more.

Our modern economy continues to generate new disparities on top of these imbalanced foundations across multiple dimensions. Inequality can manifest:

- Within companies, for instance through pay ratios between executives and workers;

- Across the capital value chain, for instance between a private equity executive and a portfolio company worker;

- Between firms, such as differences in cost of capital and access to resources between larger or fast-growing companies versus smaller and slower-growth companies; and,

- Across regions, as rural and developing areas (countries, cities, etc.) face higher costs and reduced access to capital compared to urban and developed regions.

These are just examples and not an exhaustive list, illustrating that inequality is a manifestation of a multi-layered system of disparities that reinforce one another across time and scale.

Economic inequality is constantly shaped by the structure of markets and the terms of transactions. The ways in which capital is allocated, priced, and structured and who takes what risk for a given level of return in a transaction is a lens through which economic inequality is determined. When human and social capital are undervalued in a transaction relative to financial capital, greater uncompensated risk is shifted towards those particular workers and communities, while a disproportionate share of returns accrues to the providers of financial capital. In such cases, those who bear the most exposure to operational, environmental, or social risks are often least compensated for it.

Theoretically, in free and well-balanced markets, market actors such as workers, communities, consumers, companies, and providers of capital should be able to negotiate on a relatively level and balanced playing field leading to efficient price discovery across different forms of capitals. However, vast imbalances in markets have emerged. In our modern economy, some companies, investors, and regions often wield disproportionate bargaining power, allowing them to influence the pricing of risk and return in their favor. This distorts market outcomes, biases prices discovery, and creates a self-reinforcing cycles in which economic inequality deepens over time.

Modern corporate governance and performance analysis can further entrench these dynamics – even inadvertently. While details vary across jurisdictions, corporate governance in today’s global markets has evolved to place what many would argue is a stronger emphasis on shareholder interests relative to those of other stakeholders of a company, such as workers, communities, suppliers, or consumers. The original intent of prioritizing shareholders was to prevent corporate managers from acting irresponsibly with investors’ capital, thereby addressing the principal-agent problem. This reflected an assumption that if a company performs financially well, then its stakeholders are likely sufficiently satisfied with it. A belief that financial performance is a solid representation of a company’s health also underpins the linking of executive compensation to shareholder return, a practice now deeply embedded in contemporary corporate governance.

However, investors – even long-term investors – often focus on financial performance relative to benchmarks across short-term time frames, ranging anywhere from quarterly to just a few years. This orientation can incentivize companies to externalize costs. Modern finance has not yet developed the financial analysis tools that enable diversified investors to sufficiently factor externalized costs into their risk-return analysis to inform investment decision-making. Even if they did, diversified investors 1) don’t have the capacity to engage with every single portfolio company to encourage the reduction of negative externalities, and 2) are so intermediated from workers, communities, and consumers “on the ground” that they likely wouldn’t have sufficient understanding of emerging risks and externalities, even with the best of disclosure frameworks like the one TISFD is developing.

This is why at my organization, the Predistribution Initiative (PDI), we are examining 1) corporate governance reforms that involve other corporate stakeholders such as workers, communities, and consumers in addition to traditional representation and 2) accounting and financial analysis reforms that better consider human, social, and natural capital.

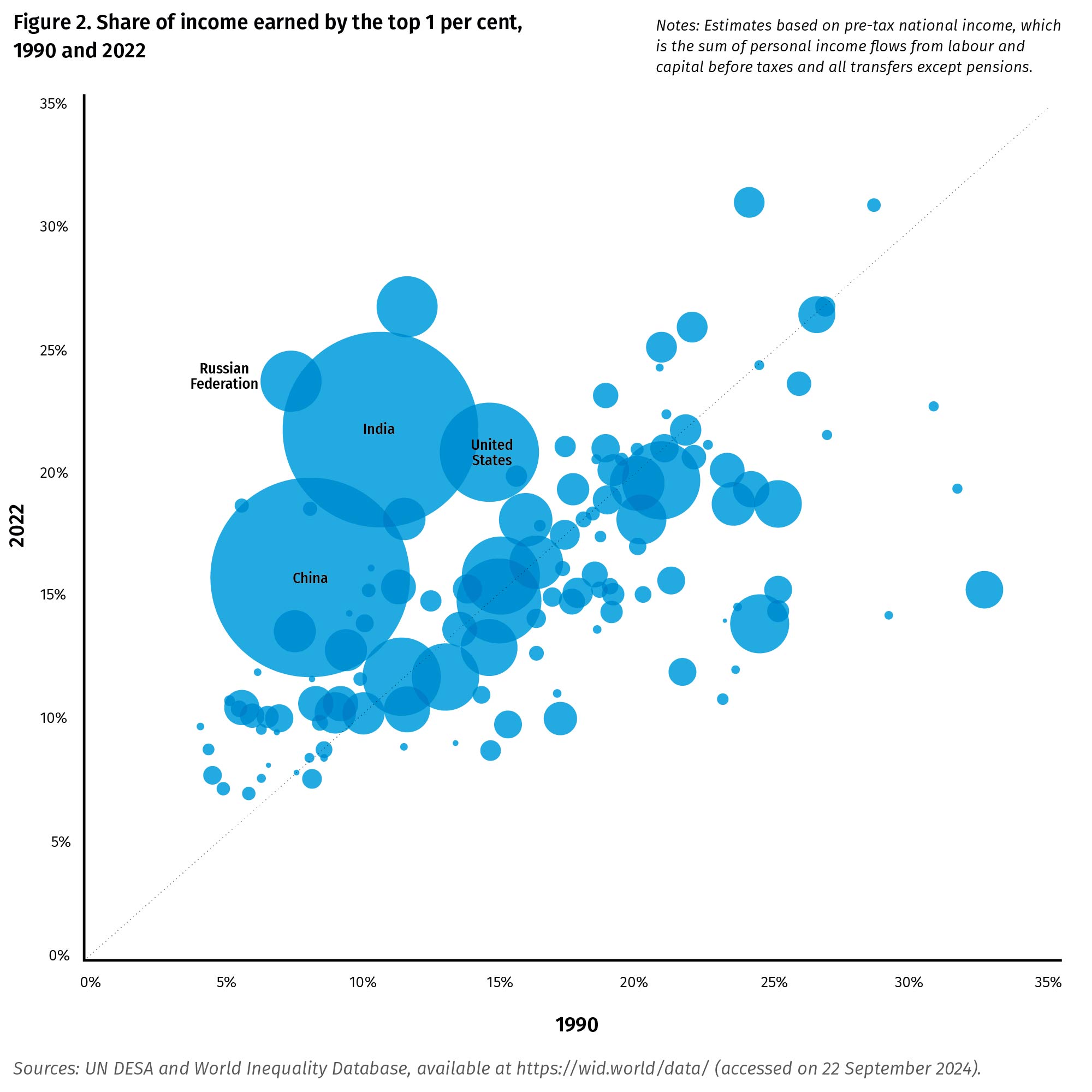

Structural dynamics help explain why, over the past decades, returns to capital have significantly outpaced returns to labor. In advanced economies, the labor share of income began trending down in the 1980s, which some attribute largely to the rise in technology and globalization. Other contributing factors exist, as well, such as deregulation, as discussed below. French economist Thomas Piketty argues that when the rate of return on capital is greater than the rate of economic growth over the long term, wealth concentration becomes structurally embedded in the economy.

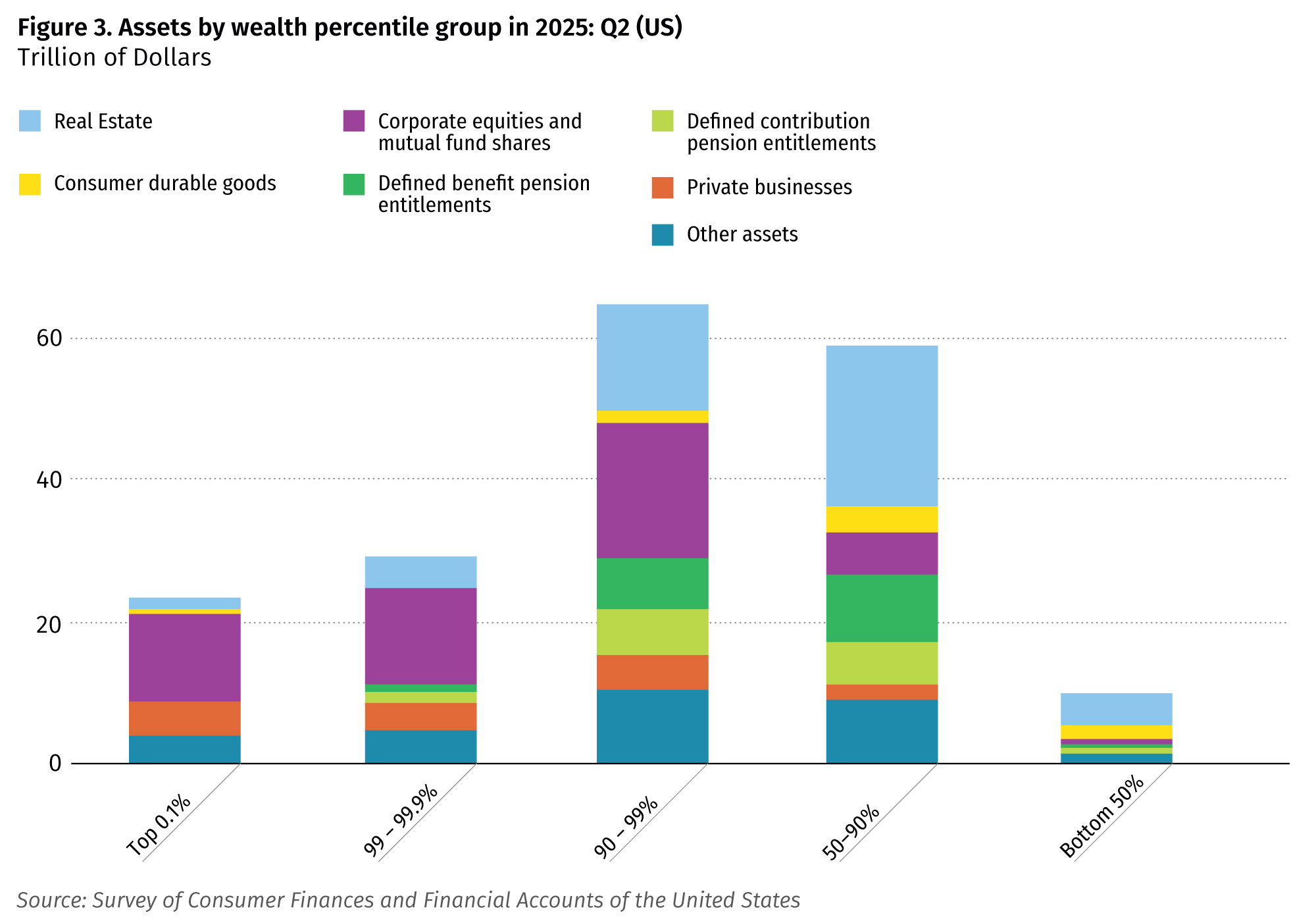

In the U.S., wealth and capital ownership have become increasingly concentrated. The top 10 percent hold about 93 percent of stock market wealth, with the richest 1 percent own approximately 50 percent of public equity markets, up from 40 percent in 2002. While the Federal Reserve estimates that 58 percent of U.S. households have some form of stock market exposure, primarily through retirement funds like IRAs and mutual funds, the concentration of ownership continues to increase.

Globally, the richest 10 percent of adults own approximately 85 percent of global household wealth, while the bottom half collectively owns barely 1 percent. In 2006, the average person in the top decile owned nearly 3,000 times the wealth of the average person in the bottom decile. Moreover, the top 1 percent own 43 percent of all global financial assets, and the “big three” U.S.-based asset managers—BlackRock, State Street, and Vanguard—collectively manage $20 trillion in assets, a significant portion of global assets under management.

Public institutions play a critical role in either exacerbating or alleviating many of these tensions. For instance, across many geographies, governments have introduced policies intended to redress historical disadvantages and level the economic playing field to reduce economic inequality. Some targeted interventions aim to reduce inequality by supporting specific marginalized groups. These targeted interventions can generate pushback when the broader population, also disadvantaged relative to the wealthy, feels excluded or overlooked by such measures, creating tensions over perceived fairness and distribution. Alternative approaches to level the playing field include redistributive policies such as progressive taxation with a focus on vertical versus horizontal inequality.

Governments have often advanced growth-oriented strategies under the assumption that a “rising tide will lift all boats.” Yet this “trickle down economics” approach has come under scrutiny for not considering distributive effects and are increasingly considered to have exacerbated inequality.

Studies suggest that deregulation in the U.S. beginning in the 1970s and corresponding with the rise of neoliberal thought out of the Chicago School of Economics has led to a loss of labor’s bargaining power and rise in financialization – or as noted previously the prioritization of financial capital above other inputs into a transaction. Weakening antitrust enforcement, loopholes, and other policy interventions which have facilitated market concentration, along with court rulings like Citizens United, have enabled companies and some investors to use their disproportionate size and resources to influence regulation. According to 2017 analysis by the nonprofit, Global Justice Now, 157 of top 200 economic entities by revenue were corporations – not countries – and top 10 corporate revenues exceeded $3 trillion.

Additionally, central banks play a significant role in shaping inequality. While low interest rates are traditionally seen as a means of stimulating economic growth in ways that benefit all, various academics, economists, and leaders across finance and other disciplines have noted that this practice also tends to ignore distributional effects and can disproportionately benefit holders of assets. Those with existing assets can borrow more easily and on more favorable terms, while rising asset prices further compound their wealth. Meanwhile, higher valuations create barriers to entry for those without assets, entrenching inequality.

Monetary interventions such as those undertaken by the Federal Reserve during the 2008 financial crisis and COVID-19 pandemic have been widely debated. While such measures stabilized markets, they also benefited investors by bailing out investments which were high risk and arguably contributed to pre-existing fragility, thereby reinforcing moral hazard and further decoupling financial markets from the real economy.

At this macro level, the broader international financial architecture also matters. The Bretton Woods system established the U.S. Dollar as the world’s reserve currency, which has been found to have destabilizing macroeconomic effects on Emerging Markets and Developing Economies (EMDEs). Recently, the Trump administration has highlighted the drawbacks of the U.S. Dollar reserve currency status in terms of its negative impacts to the U.S. economy, and has sought to depreciate the dollar to improve the attractiveness of American exports.

Regardless of intent or genuine belief in helping or harming stakeholders, there are legitimate questions arising with the public about the soundness of economic theories informing market decisions and whether technocratic decision makers are sufficiently in touch and aligned with the people they are supposed to serve. Public dissatisfaction and the perception of being left behind are fueling mistrust in political, business, and finance leaders. As imbalances in wealth and power grow more visible, and disadvantages are shared by wider segments of populations across geographies, it is increasingly unclear that markets are well-positioned to facilitate the price discovery that adequately reflects the values of human, social, and natural capital.

TISFD was established to help investors and companies understand the pathways through which the private sector contributes to inequality. As such, inequality that manifests from cultural or public sector dynamics is not explicitly in scope. However, in many cases it is difficult if not impossible to separate cultural, policy, and regulatory drivers of inequality from those of the private sector. Culture can influence what is valued in transactions and thus the distribution of risk and return. And when the private sector increasingly wields disproportionate influence over policy relative to other stakeholders, boundaries between public and private drivers of inequality are blurred.

Additionally, when considering the feedback loops or transmission channels through which inequality becomes a systemic risk to financial markets and investors’ diversified portfolios, it may be impossible, impractical, or pointless to isolate private sector drivers of inequality from cultural or policy ones. Investors seeking to understand how inequality poses a financially material risk from a systemic lens benefit from knowing what drivers they can influence, and, even where their influence is limited, from understanding the risk itself.

Finally, TISFD includes both vertical and horizontal inequality in scope. However, the rest of the article focuses primarily on vertical inequality, which is better researched and affects the majority of people globally.

Inequality as a systemic risk

When TCFD was launched, it benefitted from a strong pre-existing knowledge base – notably, the work of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and The Stern Review, which examined the economic impacts of climate change. Similarly, when TNFD was launched, it benefitted from the work of the Dasgupta Review’s findings on the economics of biodiversity.

Consultations from TISFD and other work undertaken by my own organization, PDI, indicate that market actors are seeking an evidence base for how their actions might contribute to or alleviate inequality, and how inequality affects them. A disclosure framework developed by TISFD will only be as strong and value-added as the evidence base that underpins it. Equally important is a deep understanding of the incentives that drive market actors to act on that evidence.

Together with TISFD and other partners, we are working to address these gaps. Given the vast and intersecting factors that drive inequality, there is a need for a global and multidisciplinary research network. This is currently in early stages of development. In the meantime, noteworthy work has already been done, and signals are growing stronger that inequality represents a clear and present systemic risk to financial markets and diversified investors’ portfolios. Below are some general themes which are part of the growing public discourse on inequality across geographies and political views. This article is not an effort to thoroughly document research, but rather highlight areas with strong evidence to date which could benefit from further investigation in the context of financial markets.

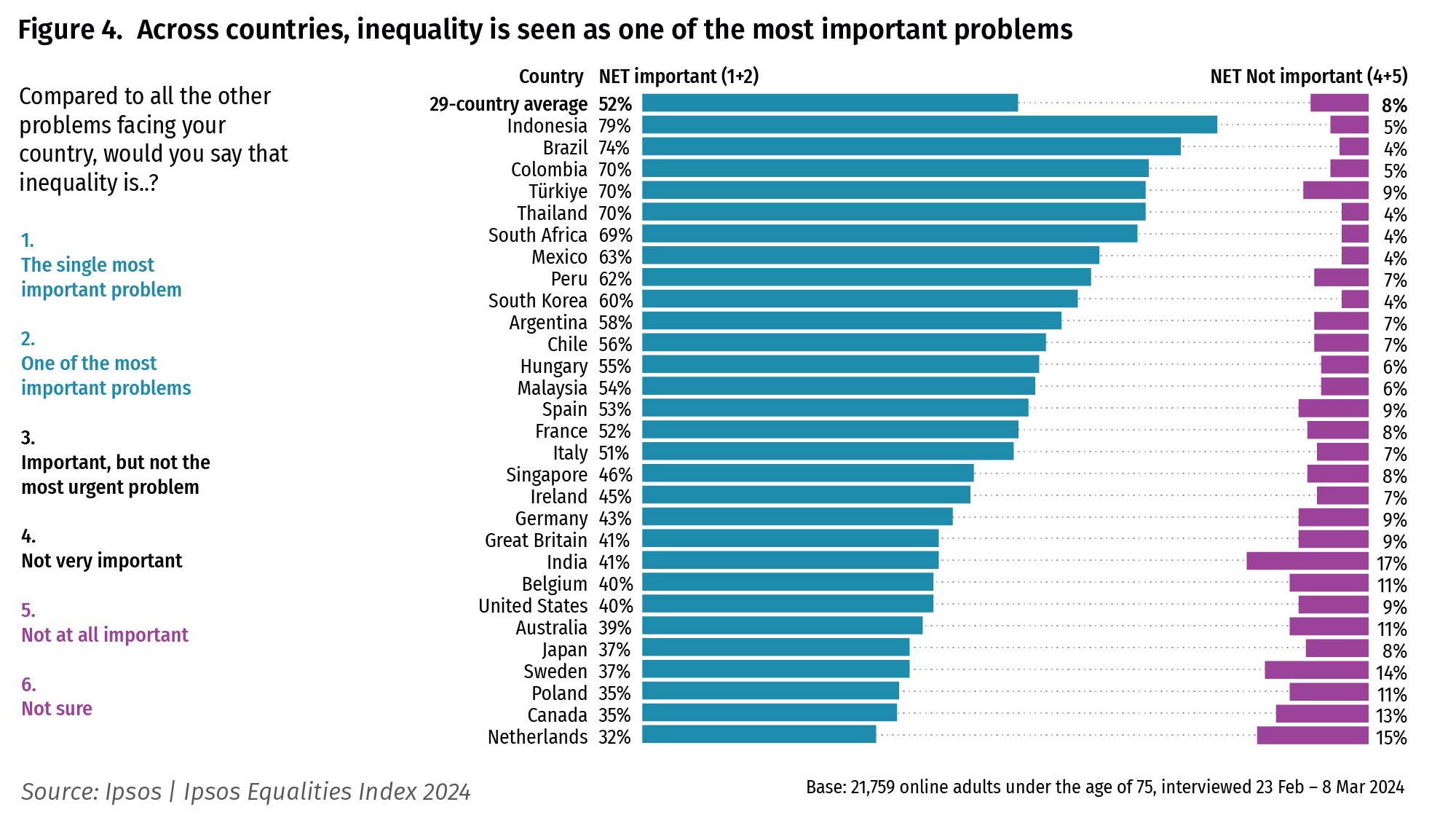

Societal instability: Perhaps most obviously, inequality can lead to social instability. From the populist movements which contributed to the fall of the Roman Republic in the 2nd to 1st centuries BCE, to pre-revolutionary France in the 1780s, to pre-revolutionary Russia, to Republican-era China in the 1900s, and Weimar Germany in the 1920s and 1930s, history shows clear tipping points when economic inequality is no longer tolerated by the public. Rising populism around the world materializing in developments such as Brexit in 2016 and recent widespread protests in mature markets and EMDEs suggest societies today may be approaching similar thresholds. Many business and finance leaders, including those mentioned earlier in this article, have increasingly voiced concern over these risks.

Recent Ipsos polls across numerous countries globally underscore this growing sentiment: a clear majority of people across generations and social classes agree that, “the main divide in our society is between ordinary citizens and the political and economic elite,” that “experts in this country don’t understand the lives of people like me,” and that “traditional parties and politicians don’t care about people like me.”

According to the 2025 Edelman Trust Barometer, fear that leaders across business, government, and media lie to the public is at an all-time high. Sixty-five percent of respondents believe that “the wealthy’s selfishness cause many of our problems.” Only thirty-six percent of respondents believe that the next generation will be better off than today. Across twenty-six countries—spanning both mature and EMDE markets— six in ten people report moderate to high levels of grievances against business, government, and the wealthy. Common sentiments include: “business and government serve only a select few,” “business and government actions hurt me,” “the system favors the rich” and “the rich are getting richer.”

Collectively, these perceptions underscore a growing sense of pessimism and belief that economic and political systems are rigged in favor of the powerful – a view encapsulated by the adage: “He who has the gold makes the rules.”

Yet the Trust Barometer also finds that rising trust correlates with greater economic optimism. Both the Trust Barometer and polling by JUST Capital suggest that improvement on issues such as treatment of workers is a high priority for those polled. Moreover, respondents in the Edelman poll report that legitimate influence is earned more by demonstrating genuine understanding of people’s needs and aspirations versus via power and position. These findings challenge the notion that mistrust in institutions is leading to a strong public preference for authoritarianism as a solution to societal problems.

The distress felt by those left behind economically manifests in diverse and often destructive ways that reverberate across society. Mistrust in large pharmaceutical and food companies, and their perceived entanglement with government, have fueled skepticism about vaccines and food safety, which have in turn led to extreme measures and ripple effects across communities, business, and financial markets. In one shocking example, outrage over the practices of insurance giant United Healthcare culminated in the murder of the company’s CEO, an act disturbingly celebrated by a notable percentage of the public on social media.

Social media commentary from both the left and right increasingly highlights the negative impacts of financialization — from declining product affordability and quality to the erosion of stable, quality jobs. Growing economic pessimism and a sense of futility and hopelessness have in turn contributed to rising rates of substance abuse, homelessness, and crime.

Research also suggests that economic marginalization is deeply intertwined with cultural alienation. Many who feel left behind economically also feel that their identity, values, and way of life are undervalued. In recent decades, urban regions around the world tend to prosper economically while rural regions have lagged. This divergence has fueled narratives of “cultural elites,” “coastal elites,” and “white collar elites,” reinforcing divisions between groups and deepening the social dimensions of inequality.

Economic distress and cultural alienation can fuel scapegoating, as certain communities or groups blame others for their losses, even if those being targeted bear no responsibility. This not only exacerbates local conflict but also undermines efforts to support historically disadvantaged communities, both within and between countries, who may themselves become scapegoats.

Martin Luther King, Jr. once noted that there would be “no genuine progress for African Americans unless the whole of American society takes a new turn toward greater economic justice,” and, “beyond these advantages, a host of positive psychological changes inevitably will result from widespread economic security. The dignity of the individual will flourish when the decisions concerning his life are in his own hands, when he has the assurance that his income is stable and certain, and when he knows that he has the means to seek self-improvement.”

Notably, research and commentary suggests that in the U.S. there is a greater public preference for predistributive rather than redistributive approaches to address economic inequality. Predistribution involves improving the systems through which wealth and productivity are created in the first place so that workers, communities, and consumers don’t have to be as dependent on redistribution through taxes, wealth transfers, and philanthropy.

Examples of predistribution include living wages and opportunities for workers and communities to build wealth, such as employee ownership of equities alongside executives and investors, or community ownership of some level of equity alongside investors in infrastructure projects they host. Freedom of association and collective bargaining, as well as other forms of stakeholder representation help achieve predistribution. Approaches to share equity with other stakeholders who take risk and create value in a transaction not only reduce wealth inequality, which is closely tied to asset ownership, but also better align the incentives of all stakeholders in a business. Doing so can help reverse the erosion of trust and reduce the “us versus them” dynamics which has manifested between the perceived elites and everyone else. Investors and companies are well positioned to help drive and benefit from these changes.

Common denominator underlying the polycrisis: The interconnectedness of modern society through advances in communication, travel, and global trade makes rising tensions increasingly systemic and mutually reinforcing. The loss of economic security – and the accompanying erosion of identity and self-worth that comes with it – not only happens within countries, but across them. While evidence suggests economic inequality is driven in part by unfettered globalization, the shift toward drastic protectionism risks throwing the proverbial baby out with the bath water. Such extreme responses have fueled trade wars, exacerbated geopolitical tensions, and weakened public and political willingness to support international development and aid.

Economic insecurity also contributes to political gridlock on pressing global challenges, particularly those, like climate change and nature loss, that require coordinated negotiation and compromise. As PDI’s recent manifesto argues, economic inequality lies at the core of the polycrisis. Achieving a broadly shared sense of economic security, dignity, and agency is essential for unlocking effective and lasting solutions to these interlinked global challenges.

Financial instability: While many recognize that the polycrisis can lead to financial instability, economic inequality itself is also a driver of financial instability. Across households, firms, and regions or countries, inequality in all its forms reflects deeper patterns of market concentration and power imbalances. These dynamics can foster asset bubbles, credit crises, and market collapses that amplify contagion risks and undermine the effectiveness of monetary policy.

At the household level, wealth concentration exacerbates instability through its effects on spending and saving behavior. The marginal propensity to spend among wealthy households is far less than among lower-income groups. As a result, excess savings among the wealthy suppress interest rates and fuel lending to sustain consumption of those less well-off. Research by Atif Mian, Amir Sufi, and colleagues has suggested that such dynamics were major contributing factors to the 2008 housing and Global Financial Crisis, revealing deep challenges shared by communities, businesses, investors, and policymakers and regulators—including central banks whose mandates typically include a focus on financial stability.

More recently, Moody’s Analytics found that nearly half of U.S. consumer spending is driven by the top 10% of households. This poses further challenges for central banks, as my colleague, Raphaele Chappe, and I outline in our recent blogpost, “The Breakdown Between Wages and Inflation – Part 1: Exploring the Potential Role of Wealth Inequality as a Driver of Inflation and Market Instability.” In an economy where so few workers are paid a living wage and able to make ends meet, it is increasingly unlikely that wages are driving inflation. And yet that relationship sets the foundations for monetary policy, with implications for interest rates, financial stability, and trajectory of inequality itself.

At the firm level, significant research documents the risks posed by monopolies, oligopolies, and corporate concentration. While many investment strategies pursue companies with strong competitive “moats,” the externalities of this approach are often overlooked and not yet accounted for by financial actors.

As highlighted by the American Economic Liberties Project (AELP), Balanced Economy Project, and in books such as The Myth of Capitalism, Monopolized, and Goliath, concentrated market power yields several interrelated dynamics that carry systemic costs:

- Limited competition and therefore pricing power disadvantages consumers: For instance, research from the Balanced Economy Project shows that the world’s largest firms have charged markups averaging 43 percent since 1995, versus 24 percent among the smallest 50 percent of firms.

- Disproportionate access to resources like technology, algorithms, and data by dominant firms reinforce their position: This creates high barriers to entry for smaller companies and leads to biased and unfair investment, procurement, and pricing strategies that favor incumbents over new entrants.

- The combination of the previous two issues can also disadvantage suppliers to the larger companies.

- Preferential access to capital and lower financing costs further entrenches the dominance of larger firms: In addition to contributing to the aforementioned dynamics, this can enable practices such as “killer acquisitions”—where large firms acquire emerging competitors to stifle innovation, and other anti-competitive behavior which can in-turn destroy emerging competition. Similar concentration patterns appear in housing markets, where institutional investors’ ownership of residential property raises barriers for families and individuals seeking to buy homes.

- Dominant firms benefit from reduced pressure to produce quality goods and services: In less competitive markets, firms face weaker incentives to innovate or ensure high standards. In sectors where safety is critical, such as healthcare, hospital market concentration has been linked to higher mortality rates and poorer patient outcomes due to diminished quality competition.

- When there are fewer employers, worker bargaining power decreases and wages and compensation often decrease through “monopsony” dynamics: This not only harms workers but also constrains aggregate demand, reinforcing the broader feedback loops between inequality and economic instability.

While solutions to addressing market concentration have centered on antitrust regulation and enforcement, these interventions alone may not sufficiently address deeper structural drivers, particularly those rooted in the architecture of financial markets. For instance, our past research explores how the concentration of capital amongst large asset owners and allocators since the 1950s has led to larger fund managers in private markets, which can lead to larger deal sizes. This can leave an investment gap for smaller companies and fund managers, which are arguably needed for dynamic, diversified, and well-functioning markets. Furthermore, in public equities, emerging research suggests that the rise of passive investing and index funds may lead to price distortions in securities which can unfairly advantage larger players in the dominant indices.

The combination of these factors may contribute to high asset prices and potentially asset bubbles. Additionally, in private equity, the concentration of capital among a small number of managers chasing similar deals may inflate valuations and incentivize the use of leverage to magnify returns if companies are already bought at high valuations, thereby contributing to potential debt crises.

These firm- and market- level dynamics intersect with those at the household level. As savings increasingly flow into financial assets—often through vehicles seeking higher returns with riskier investments—valuations rise further, more capital is allocated to less-regulated nonbank sectors, and there is a greater supply of credit throughout the system, increasing borrowing by both lower-income households and businesses, and deepening systemic vulnerabilities.

The scale and market power of monopolies and oligopolies renders them less sensitive to fines, penalties, and reputational risk, weakening traditional mechanisms of accountability. This dynamic erodes the financial materiality link that underpins corporate governance and responsible investment decision-making.

Finally, at the geographic level, urban centers and mature economies typically are wealthier with more liquid markets than rural areas and less mature economies. The former can thus be more attractive to many investors. Despite significant research on the overlooked opportunity of investing in underserved markets, investors often believe they can achieve comparable or stronger returns in developed markets with less risk than for many EMDEs – frontier markets in particular. Reasons for why the perceived risks of these markets may be greater than actual risks have been well-documented.

However, considering the systemic risks of not allocating adequately priced capital to these markets could shift their risk-return profiles. If EMDEs do not have sufficient capital at a manageable price to invest in their own development, these regions could face deterioration that will destabilize global markets and therefore pose threats to diversified investors’ portfolios. For instance, due to a lack of access to reasonably priced capital, certain EMDEs may face physical climate risk that jeopardizes global supply chains and catalyzes widespread inflation, as well as mass migration that destabilizes developed market economies, and therefore investors’ diversified portfolios.

Overall, the externalities arising in financial markets from concentrated wealth and inequality pose systemic risks to capitalism itself. While some might hold the belief that markets are a zero-sum game, ultimately if looked at systemically, they are not. Inequality and systemic risk are both about the distribution and management of risk and return, and a balance is needed to avoid the system destroying itself.

Conclusion: Recommended next steps

At a time when rapid advances in technology have the potential to exponentially accelerate existing trajectories, these issues are more urgent than ever.

The various facets of economic inequality are vast, and to address them, a robust effort is needed to synthesize existing research, identify gaps, and narrow gaps. This requires two areas of distinct investigation: evaluation of the pathways through which companies and investors affect inequality, and the feedback loops through which they are affected by it. Importantly, this agenda also includes development of new financial analysis tools and methodologies to capture systemic risk in investment decision making, as well as accounting tools at the corporate level to better value and consider human, social, and natural capital. Beyond investors and companies, this information and these tools can help policy makers, regulators, ratings agencies, financial advisors, and workers, communities, and consumers in their efforts, as well.

It is also critical that this collective effort not reproduce the very hierarchies it seeks to dismantle. It must value co-creation and draw deeply from the lived experiences and insights of workers, communities, consumers, smaller enterprises, and economically disadvantaged regions. Systems change cannot be top-down.

Indeed, the multistakeholder governance approach that TISFD has adopted in its own structure can serve as a model for companies and investors seeking to co-create solutions together with their own stakeholders. Such an approach ensures that any global framework developed is applied in a locally grounded and contextually relevant manner. Ultimately, fostering a culture of systemic stewardship is essential. Only through collaboration across sectors, stakeholders, and societies can we begin to confront the polycrisis facing humanity and our planet.